Mahler (in/a) Cage | Casetta di Composizione – Sergio Armaroli & Alessandro Camnasio

A musical physiognomy of the soundscape

Gruen 203 | Audio CD (+ Digital) | Digital > [order]

Reviews

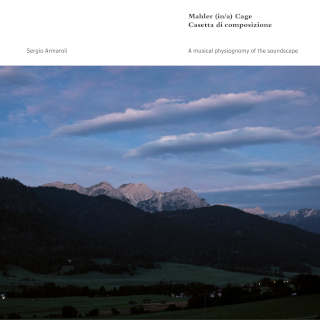

The Mahler (in/a) Cage field recording work involves the recording, in situ, from the Casetta di composizione (Composition house) in Dobbiaco/Toblach (Bozen), of the soundscape in which Gustav Mahler composed his last works from 1909 to 1911 and in particular The Song of the Earth (Das Lied von der Erde). The recording session took place over two summer days, from July to August 2020 from 5 am onwards, in the period of the year in which Mahler himself re sided in Dobbiaco to compose at the beginning of the century.

Mahler (in/a) Cage is a field recording work, a process of possible reconstruction of a hypothetical and natural soundscape, within Mahler’s music or rather his musical imaginary following some archetypal signals (e.g. cowbells, birdsongs). All this is traced back to the composition of John Cage Sculptures Musicales (1989): “Sounds lasting and leaving from different points and forming a sounding sculpture which lasts” (Marcel Duchamp). An exhibition of several (sonic sculptures), one at a time, beginning and ending “hard-edge” with respect to the surrounding “silence”, each sculpture within the same space the audience is. From one sculpture to the next, no repetition, no variation. For each a minimum of three constant sounds each in a single envelope. No limit to their number. Any lengths of lasting. Any lengths of non-formation. Acoustic and/or electronic [Peters Edition EP 67348].

Tracklist:

1. The sound of the earth: at dawn – [0:00 to 7:31]

2. Characters – [7:31 to 19:16]

3. Variant and shape of water – [19:16 to 24:41]

4. Nel mezzo – [24:41 to 34:54] ~ Dialectical Cesura

5. Zoo: animal symbolism – [34:54 to 43:39]

6. Casetta di composizione – [43:39 to 46:39] / 6A [46:39 to 49:17] ~ Subjective \ “… nervous susceptibility”

7. The long look: forever \ Ewig

(A Musicall Banquet, 1610, no. 10) – [49:17 to 1:14:00]

Excerpts:

MP3 | 1 & 2

MP3 | 2 & 3

MP3 | 7

MP3 | 7

7 Tracks (74′00″)

CD (300 copies)

Concept Sound: Sergio Armaroli

Sound Engineer: Alessandro Camnasio

Photographic action (in the soundscape): Roberto Masotti

Recordings made in Dobbiaco/Toblach (Bozen)

on 19, 20, 21 August 2020

Mixing, Synthesis and Audio Editing by Alessandro Camnasio

Field Recording by Sergio Armaroli and Alessandro Camnasio

Photographic concept in soundscape by Roberto Masotti

Artwork by U9 visuelle Allianz

Track (1) Mahler(in/a)CAGE \ Casetta di Composizione

ISRC QM4TX2177634

Field Recording Series by Gruenrekorder

Germany / 2021 / Gruen 203 / LC 09488 / UPC 196006298074

textura

The booklet included with the physical CD release of Mahler (in/a) Cage, the latest addition to Gruenrekorder’s Field Recording Series, provides helpful context for the recording. In the “Preludio,” the work is described as a “possible reconstruction of a hypothetical and natural soundscape, within Mahler’s music or rather his musical imaginary following some archetypal signals (e.g. cowbells, birdsongs).” Even more helpful are notes by Alessandro Camnasio, credited as the sound engineer for Italian sound artist Sergio Armaroli’s project. Referring to the process by which details at the site were first captured and then subjected to shaping in the studio, he states that de-noising processing was used to purge the field recordings of car and machinery noises in order to “recreate a soundscape closer to the one that Mahler probably heard during his stays in Dobbiaco.” Further to that, water sounds were coloured with resonances tuned to specific frequencies from Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth) and the soundscape sculpted to reconstruct “Mahler’s subjective listening experiences in those places.”

Described in simpler terms, Mahler (in/a) Cage appears to be an attempt to fashion a facsimile of the outdoors setting Mahler immersed himself within Dobbiaco (Toblach in German) in Northern Italy during the period from 1909 to 1911 when he composed his final works. Adding to that, some semblance of the composer’s inner experience is incorporated too. Armaroli even went so far as to schedule the field recordings to be gathered over three days in August 2020, the same time of the year when Mahler resided in Dobbiaco to compose. The recording thus offers a striking re-imagining in soundscape form of the physical environment he was exposed to and the inner states he experienced in response to it during his stay.

Unfolding across seven parts, the seventy-four-minute soundscape emerges, appropriately enough, from silence at dawn with rustlings of the land, wind, and bird noises gradually fleshing out the sound field. Moving from vibrant activity on land, we’re submerged for the five minutes of “Variant and shape of water” before returning to the surface for further explorations of the area, encounters with wildlife during “Zoo: animal symbolism,” and eventual arrival at the actual composition house (and thus metaphorically inside Mahler’s mind) in “Casetta di composizione”.

Admittedly, the cowbells that emerge within the densely layered second part, “Characters,” more evoke Mahler’s sixth symphony, composed during the summers of 1903 and 1904, than Das Lied von der Erde, created from 1908 to 1909. That detail notwithstanding, the sound element will evoke Mahler for aficionados of his work, regardless of the specific work or time period with which it’s associated. I’ll also confess that—at the risk of seeming too much of a literalist—there are moments where I would have liked to have heard slightly more direct reference to Mahler’s music in the soundscape, a desire cued perhaps by Camnasio’s statement that certain key pitches and thematic elements in Das Lied von der Erde were used to enrich the material. While those pitches do audibly hover in the background of “The long look: forever \ Ewig,” a faint trace of the singer’s repeated “Ewig” at the end of “Der Abschied” (“The Farewell”), for example, might have been worked into the soundscape’s closing section to render the connection more explicit. Even so, Armaroli’s creation does impress as an inspired, original, and imaginative homage to the composer.

link

Guillermo Escudero | Loop

Gustav Mahler lived his last years in the town of Dobbiaco / Toblach (Bozen), Northern Italy, where he composed the work “The song of the earth” (“Das Lied von der Erde”) between 1907 and 1909.

This work was carried out in the period of the year in which Mahler himself resided in Dobbiaco and the purpose was to evoke the soundscape that accompanied Mahler when he composed the aforementioned work.

The recording session was completed in the summer of 2020 by the Italian Alessandro Camnasio, Italian composer, sound designer, editor and sound engineer, together with Sergio Armaroli, sound artist and vibraphonist who currently lives in Milan.

Field recordings include water, cars, animals, birds, tractors, bells, children playing, and the hum of the field being held like a drone. This exterior space in the concept of John Cage and hence the sound artists refer to it, would be a „musical sculpture“, as well as the interior space called the „House of Composition“, which would be another musical sculpture.

These soundscapes served as a source of inspiration for Mahler, but they can go unnoticed, so when relieved in a recording like this, the environment and what lives in it, is better appreciated.

link

Ettore Garzia | Percorsi Musicali

Mahler (in/a) Cage: panorami sonori fisiognomici

Sull’idea del soundscape si può certamente effettuare un’analisi temporale retroattiva per accogliere corrispondenze con il pensiero di un compositore: l’idea del vagare o passeggiare su un territorio per trovare suoni naturali da filtrare nella composizione fu una fonte d’ispirazione per molti dei compositori romantici del periodo ottocentesco. Lo fu per Schumann in Waldszenen così come lo fu indiscutibilmente per i compositori del Nord Europa che l’applicarono con soavità differenziate nella musica (da Grieg a Sibelius); un compositore come Mahler, per esempio, dimostrò di avere un amore fortissimo per alcune zone alpine frequentate fuori da Vienna, che servirono come zone-cuscinetto dell’anima: Mahler incrementò i suoi soggiorni soprattutto negli ultimi anni della sua vita, quando in essa si stavano concentrando parecchie disgrazie (la perdita della figlia, la remissione del lavoro a Vienna e soprattutto un cuore irrimediabilmente malato); il soggiorno prescelto da Mahler fu quello incantevole di Dobbiaco e gli studiosi dell’austro-boemo hanno da tempo sottolineato l’importanza di una delle sue ultime opere, la Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth) per due voci contralto e tenore più orchestra, riconoscendone un particolare valore finale, un senso di devozione alla natura con riguardo del testo poetico, posto come una riorganizzazione di poesie cinesi tradotte in tedesco. […]

link

Richard Allen | a closer listen

What did Gustav Mahler hear as he composed The Song of the Earth? This inviting question is answered by Sergio Armaroli and Alessandro Camnasio on Mahler (in/a) Cage | Casetta di Composizione, whose title refers not to putting the composer in a cage, but to John Cage, whose concepts inform the execution.

In his last years, Mahler resided in Dobbiaco (Bozen), writing in the evocatively named Composition House. Armaroli and Camnasio begin recording outside the house and gradually work their way toward, and then in. A distant hum marks “The sound of the earth: at dawn,” punctuated by birds as they begin to awake and sing: the call to the composer to awake, fling open the sashes and begin to write. But perhaps Mahler had a different start in mind: to walk the meadows and drink in the soundscape. Would Mahler have brewed a cup of fine Italian coffee, or donned a cap and perhaps a pen? Would he have stopped to appreciate the sound of the day’s first cowbell, anticipating the arrival of more? Were the creative thoughts already beginning to unfold?

Behind the birds and bells, the chugging of a distant train can be heard. These were the years of socialism and Futurism, the halcyon years before the Great War, although the Austrian composer would pass away before the conflict began. The train spoke instead of travel, of open vistas, of possibility, just as the church bells served as a reminder of time, calling the mind back from its wanderings like a parent calling a child for breakfast.

And now the water, such water, sparkling and flowing, suggesting the smooth edges of a succulent symphony. Whether house shower or stream, the sound is known to produce inspiration, a white noise that filters distractions. Soon it envelops the soundscape like an orchestral crush.

And then the house, in the words of Cage, “a sounding sculpture that lasts.” The passage of wind through cracks, the echo of boots on earth, the fraying edges and solid understructures. Someone is hammering, a sound Mahler might not have appreciated as he tried to corral his scattering notes. But Mahler is hammering too: hammering out his composition in fits and fleets, the Song of the Earth, the great outside partially reimagined as he works inside, creating impressions that others would continue to embrace over a century later. Not that he was thinking that far ahead; already aware of his own mortality, he was writing of the fear of death, followed by acceptance, caving to the great eternal.

Finally, continued life ~ a family, perhaps wandering the grounds, a symbol of the endurance of time. New creatures bleat and caw, perhaps the descendants of those met by Mahler. An audible joy is apparent. Mahler’s music has entered the flow suggested by the stream, and the earth has continued to sing.

link

Frans de Waard | VITAL WEEKLY

This new Gruenrekorder release is one of those releases that I don’t know about. Now, suppose you don’t read any of the text, inspect the cover, and know anything about the musicians; what do you hear? Field recordings from the countryside, I would say. Water, cars, some animals, tractors, children are playing. Did I at any point think this is the house in which Gustave Mahler composed ‚Das Lied Von Der Erde‘, among other works (his last)between 1909 and 1911. I have no idea where to find Dobbiaco/Toblach (Bozen) on the map, and I pride myself on some geographical knowledge. Sergo Armaroli visited the place and recorded his sounds, according to John Cage’s ideas as laid in ‚Sculptures Musicales‘, „an exhibition of several (sonic sculptures), one at a time, beginning and ending „hard-edge“, concerning the surrounding „silence“, each sculpture within the same space the audience is. From one sculpture to the next, no repetition, no variation. For each, a minimum of three constant sounds, each in a single envelope. No limit to their number. Any lengths of lasting. Any lengths of non-formation. Acoustic and/or electronic“. The booklet mentions more names, R. Murray Schaefer and Adorno. Oddly enough, Alessandro Camnasio is responsible for mixing the music and in a short explanation, he says this work is the typical electro-acoustic composition, also using synthetic sounds. The question is, of course, are we hearing what Mahler may have heard? Surely not, I’d say, as there wasn’t much synthetic sound in his days. Although I am a bit sceptical about the whole project, I immensely enjoyed the final piece, ‚The Long Look: Forever/Ewig‘, in which insect sounds seem to mingle elegantly with synthetic sounds, and it all becomes more than sonic snapshots from a location that perhaps not many have visited and may lose it’s meaning, without knowing the proper context. Having said that, I quite enjoyed this release, but mainly for its approach to the world of field recordings. I always enjoy hearing, and I can dispense with the bigger context.

link

Mahler (in/a) Cage | Casetta di Composizione

@ ACL 2021 ~ Top Ten Field Recording & Soundscape

The natural world existed long before the creation of instruments: music made by wind and waves, birds and beasts. During the pandemic, many people have rediscovered the aural joys of nature: music that is always playing, and that can best be heard without headphones. Field recording artists capture these sounds like others do photographs, and share their sonic souvenirs with the world.

This year’s picks travel from the heat of a volcano to the frigidity of Antarctica, with pit stops in between: rainforests, greenhouses, hidden islands and rivers. Some of these sounds exist a long plane ride away; others have been lost forever; still more wait just outside our windows, waiting to be heard. […]

Mahler recorded Song of the Earth in the cozy environment of the Composition House (pictured at the top of this article). Over a century later, Armaroli and Camnasio attempt to recreate his sonic environment using concepts from Cage. Toward the end of this imaginative reconstruction, the strains of Mahler’s labor waft through an elaborate tapestry of rural sounds. (Richard Allen)

link