Everyday Infrasound in an Uncertain World | Brian House

Gruen 228 | Vinyl (+ Digital) | Digital > [order]

Orders inside of US please go through Bandcamp

Reviews

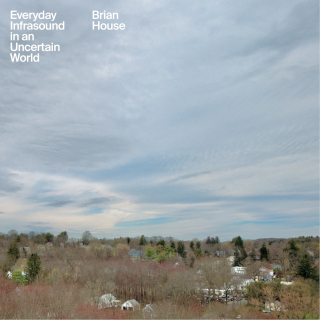

Everyday Infrasound in an Uncertain World

Even though you can’t hear it, infrasound fills the air. And because the atmosphere doesn’t absorb it like regular sound, infrasound comes from hundreds, if not thousands, of miles away. If humans could perceive frequencies lower than 20 Hz, then changing ocean currents, wildfires, turbines, receding glaciers, industrial HVACs, superstorms, and other geophysical and anthropogenic sources from across the planet would be part of the quotidian soundscape of our lives, wherever we might be.

I made this recording in the small town of Amherst, Massachusetts. I sped it up by a factor of 60: 24 hours becomes 24 minutes, raising the pitch by almost six octaves and making infrasound audible. Although we might think we hear something familiar when listening to this album, only its very highest sounds could have been detected with an unaided ear.

Since ordinary microphones cannot pick up frequencies this low, I constructed infrasonic “macrophones.” If a microphone amplifies small sounds, a macrophone brings large sounds with long wavelengths into our perceptual range. Each consists of a wind-noise reduction array leading to a microbarometer and a data recorder. I based the design on what the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Organization uses to detect distant warhead tests. In this case, however, we’re listening to a planet in transition.

This work germinated in Oregon amid an unprecedented season of wildfires. It developed along with my chronic illness, Lyme, a tick-borne disease that has become more common as a result of warming winters. My young son watched over the recording process; our ancestors mined coal. For me, it’s not just a matter of hearing what is novel to the human ear, but of encountering those agencies greater than our own that connect us through the atmosphere.

Side A – Day, 6am–6pm [12:00] | MP3

Side B — Night, 6pm–6am [12:00]

2 Tracks (24′00″)

Vinyl (300 copies)

3 macrophones placed equilaterally at 100 ft

Pressure range: +-25 Pa (0.001 Pa / 0.01 s)

Recording samples per second: 100 Hz

Wavelengths captured: 28.12–4,658.79 ft

Measured frequencies: 0.25–40 Hz

Playback frequencies: 15–2,400 Hz

Lon/lat: -72.506248333,42.367743333

Concept, construction, programming, and audio production: Brian House. Mastering: Jon Cohrs. Design: Partner & Partners. Illustration: Lincoln Nemetz-Carlson. Studio assistance: Zac Watson, Andrew Kim, Ziji Zhou. With support from: Creative Capital, Amherst College, J & K Altman Foundation. Thanks: Ethan Clotfelter, Ben Holtzman, Leif Karlstrom, Theun Karelse, Lucia Monge, the art department at Lewis & Clark, and the Columbia Center for Spatial Research.

Field Recording Series by Gruenrekorder

Germany / 2025 / Gruen 228 / LC 09488

Holger Adam | skug – MUSIKKULTUR

Nüchtern betrachtet, lässt sich, was als Musik zu Gehör kommt, auf mathematische bzw. physikalische Grundlagen zurückführen. Klang besteht aus Frequenzen, Schallwellen im für Menschen hörbaren und nicht hörbaren Bereich. Infrasound wiederum besteht aus Niedrigfrequenzen, die uns alltäglich umgeben, wir aber nicht wahrnehmen können – es sei denn, sie werden aufgezeichnet und anschließend in den Frequenzbereich übersetzt, der dem menschlichen Ohr zuträglich ist. Wie dies genau vonstattengeht, ich kann es nicht wirklich erklären. Weder in Physik noch in Mathematik war ich besonders gut in der Schule. Aber Brian House hat sich mit einer entsprechenden Versuchsanordnung darangemacht, Infrasound einzufangen, hörbar zu machen und als Musik zu veröffentlichen. Im Begleittext zu »Everyday Infrasound In An Uncertain World« erläutert House sein Vorgehen und kontextualisiert seine Experimente, sodass auch nicht naturwissenschaftlich geneigten Menschen einleuchten kann, was das soll. Die Veröffentlichung kreist um eine paradoxe Situation. Die physikalischen Phänomene können in ihrer eigentlichen Form zwar dokumentiert, aber (ästhetisch) nicht rezipiert werden – zumindest nicht mit den Ohren. Die zugrundeliegenden Datensätze können aufgenommen und gelesen, aber nicht gehört werden. Was im Anschluss an die Bearbeitung dieser Daten tatsächlich gehört werden kann, ist eine veränderte, an den menschlichen Wahrnehmungsapparat angepasste Form dieser geisterhaften Schallwellen. Die Übersetzungsarbeit von House dient, so könnte man sagen, der Ermöglichung der Erfahrung einer ansonsten nicht wahrnehmbaren Realität. In eigenen Worten spricht er von »encountering those agencies greater than our own that connect us through the atmosphere«. In diesen Gedanken berühren sich sozusagen Physik und Metaphysik; Gottesbeweise werden ja schon lange nicht mehr nur von gottesfürchtigen Mystiker*innen oder Religionswissenschaftler*innen unternommen, sondern die Frage, was die Welt im Innersten zusammenhält, motiviert auch experimentelle Physiker*innen – oder Klangkünstler*innen. Idealerweise eint alle diese Forschenden eine gewisse Demut vor der Schöpfung bzw. dem, was der Fall ist, eine wissenschaftlich-ethische Haltung, die logisch fundiertes und spekulatives Denken mit einem grundsätzlichem Respekt vor allem, was ist und nicht (oder noch nicht entdeckt) ist, verbindet – denn man weiß ja nie (alles)!

Angesichts fortschreitender globaler Umweltzerstörung und sonstiger weltweiter Ausbeutungs- und Unterdrückungsszenarien ist es nicht die schlechteste Übung, zurückzutreten, innezuhalten und zuzuhören. Aber diese vornehmen Gesten sind oft leider nicht besonders wirkungsvoll gegenüber dem ignoranten und machtvollen Gehabe all derer, die meinen, sie wüssten, wo es langzugehen hätte. Dem Vormarsch rechter Ideologien sowie der ihnen entsprechenden politischen Ausdrucksformen und gesellschaftlichen Trends im Dienst der Gegenaufklärung fallen täglich Errungenschaften demokratisch-aufgeklärter Gesellschaften zum Opfer – nicht nur in den durch Trump und seine Kollaborateur*innen tyrannisierten Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika. Rücksichtslose Wichte wie Elon Musk geißeln Empathie als Schwäche und auch wenn ich wissen kann, dass solch markigen Sprüche nicht nur dumm und inhaltlich falsch sind, so sind sie zugleich Ausdruck einer um sich greifenden Enthemmung: Die, die meinen, nichts mehr sagen zu dürfen, sind ja genau diejenigen, die in ihrem grenzenlosen Ressentiment das Maul am weitesten aufreißen. Eine eigentlich lächerliche und durchschaubare, aber leider auch erfolgreiche Strategie, Aufmerksamkeit zu erlangen. Demgegenüber kämpft der randständige Sound-Artist auf verlorenem Posten und wird im Verhältnis nur wenige erreichen. Aber in diesem gesellschaftlichen Spannungsfeld, einer Gegenwart voller dummdreistem Getöse und hasserfülltem Geschrei, steht er mit seinen feinen Antennen und anderen Apparaturen, die er zum Einsatz bringt, um Menschen für das zu sensibilisieren, was sie erfahren können, wenn sie sich darauf einlassen. Wenn sie die Gelegenheit wahrnehmen, zuzuhören. Im diesem relationalen Charakter, der das Verhältnis der Menschen zu sich und ihrer Umwelt zur Voraussetzung hat und erforscht, ist die philosophische Bedeutung von Sound-Art aufgehoben. Hierin erfüllt sich auch ihr sozialer Sinn, wenn man so will. Das weiß auch Brian House, wo er darüber sinniert, was uns miteinander verbindet, und so seine Übersetzungsarbeit als Kommunikationsangebot rahmt, als Einladung zum Dialog. Es ist ein Jammer, dass Klangkunst als Bestandteil der Populärkultur an dieser Stelle einen verhältnismäßig schweren Stand hat. In der Literatur oder in Filmen, die thematisch der Science-Fiction zuzurechnen sind, scheint es leichter zu sein, solche Perspektiven zu vermitteln. Vielleicht liege ich da auch falsch, aber das geisterhafte Gebrumme, das sanfte Dröhnen der Aufnahmen von Brian House ist »an sich« wenig spektakulär. Die Hürde, auf »Everyday Infrasound In An Uncertain World« mehr als nur »Geräusche« wahrzunehmen, ist relativ hoch. Das ist in der Auswertung und Betrachtung von Radioteleskopaufnahmen aber auch nicht anders. Die Arbeit, solche Eindrücke verstehen zu wollen und einzuordnen, die muss man sich schon machen. Sie erfordert einige geistige Klimmzüge, aber die Anstrengung lohnt sich. Ich habe in der Besprechung versucht, vorzuturnen. Jetzt sind Sie dran.

link

Colin Lang | Musique Machine

Brian House has put together something of an album, the contents of which really pass over anything resembling the possibility of a critical appraisal (more on this in a sec). The concept of Infrasound –– the auditory information that exists below the threshold of human perception – is a topic closely wed to larger concerns of situatedenss, environmental awareness, and the like. So when Brian House, a professor of such things, set out to construct microphones capable of capturing such phenomena, the die was essentially cast. In other words, House, fully cognizant of this fact, had no real control over what it is said microphones would relay. In order to render these findings perceptible, House used an old chestnut of tape recording: speed things up, which will de facto pitch things up to a frequency range that our little lugs can hold onto.

Now the point about being beyond the purview of any critical apparatus (I’ve been called worse) should begin to come into focus. How is one to make a judgment around the breeze in a forest, or the sound of waves crashing? „Ah, nice enough, but I prefer the way air moves through a more dense arrangement of trees.“ I am walking through the open door, I realize, but it is all to say that what is left to talk about here is House’s concept, and perhaps its implementation. Split into two, 12-minute tracks, each comprised of a sped-up segment of 12 hours, where each minute is roughly equivalent to 1 hour of the day in question. Much to my surprise, without knowing it, the nighttime portion sounded much more night-y than the former, though pitch shifting will do funny things to your perception. It made me wonder why speed and pitch still had to be married to one another, given so much in the world of electronic composition that has worked to separate them? Finally, given the hallucinatory nature of these phenomena, why not keep going with their manipulation into the realm of the audible? There is not much truth to material anyway, but I digress.

Fans of field recordings, passive microphonics, and other niche listening experiences, will certainly find a bizarre, if familiar world of acoustic phenomena on Everyday Infrasound in an Uncertain World.

link

The Wire Magazine (The Wire 502)

In Amherst, Massachusetts, more than 150 years ago, Emily Dickinson wrote of her appetite for silence. Brian House, on a visit to the poet’s home town, made recordings of low frequency noises pervading the air yet ordinarily inaudible to the human ear. These pulsations of infrasound may have originated in remote events: wildfires; turbulence in oceans; some distant glacier receding. For Dickinson, all would have been subsumed into her consciousness of silence. But House sped up his recordings, condensing a day into 24 minutes, rendering infrasound audible in the process. Everyday Infrasound In An Uncertain World is a notable document in terms of its conceptual and technological ingenuity. The title also registers House’s sensitivity to pressing ecological issues that reverberate through our lives. Dickinson, habitually focused on that interface where sensory awareness melds with a world beyond its apprehension, would surely have found poetry here.

link

Rigobert Dittmann | Bad Alchemy Magazin (131)

Zitat: Wenn der Mensch Frequenzen unter 20 Hz wahrnehmen könnte, wären Veränderungen der Meeresströmungen, Waldbrände, Turbinen, zurückweichende Gletscher, industrielle Klima- und Lüftungsanlagen, Superstürme und andere geophysikalische und anthropogene Quellen auf der ganzen Welt Teil der alltäglichen Geräuschkulisse unseres Lebens, wo immer wir uns auch befinden. BRIAN HOUSE legt damit die Basis für Everyday Infrasound in an Uncertain World (Gruen 228, LP). Mit in Amherst, Massachusetts, mit ‚Macrophones‘ eingefangenem Infraschall bei Tag – ‚Day, 6am–6pm‘ [12:00] – und bei Nacht – ‚Night, 6pm–6am‘ [12:00]. Wobei er die 24 Stunden auf zweimal 12 Minuten gerafft hat. Das ergibt eine wie geträumte Phonographie aus schlurchenden Schüben von dumpf dröhnenden Klangwolken, glissandierenden Strichen und flötenden Lauten mit einem Anklang von EVP, von ‚paranormalen Tonbandstimmen‘, oder von Walgesang. Eine heimliche und merkwürdig zarte Musik, die die Welt da für sich macht. Dabei geht es House, der am Amherst College Kunst lehrt, um den Climate Change, der auch da stattfindet, wo man es nicht ’sieht‘ und ‚hört‘. Mit „Animas“ (2016) hat er den katastrophalen ‚2015 Gold King Mine waste water spill‘ thematisiert, mit „Terminal Moraine“ (2021) die Gletscherschmelze und unser fehlendes Zeitgefühl, mit „Post-Natural Pastorale“ (2022) New Yorks Freshkills Park als renaturierte Mülldeponie. Man sollte auf ihn hören.

link

framework radio | #948

phonography / field recording; contextual and decontextualized sound activity

presented by patrick mcginley

Everyday Infrasound in an Uncertain World | Brian House

Broc Nelson | Everything Is Noise

We are music nerds at Everything Is Noise, each of us geeking out weekly, if not daily, about some obscure band or another, and this enthusiasm and passion is what has built and maintained this website. Some of us are musicians, but all of us have opinions on music regardless of our level of understanding music. I am not much of a musician, but I have become fascinated with how music works, or more specifically, how sound works. When I started learning about synthesizers, I took a step back from years of listening to music to appreciate that the building blocks of every sound, whether the strum of a guitar, the pop of a snare drum, the notes from a vocalist, or literally any other sound, musical or not, are just waves. Synthesizers allow you to shape and warp and modulate the wave length, shape, frequency, etc., of a relatively simple sound wave into potentially any sound you can imagine or wish to replicate. Thinking about sound this way can be overwhelming, but also kind of simplifies our music obsession into boiled-down clichés, like, ‘music is just wiggly air,’ or ‘Everything Is Noise.’

What I had not initially considered, and I imagine many people don’t, when thinking about the science of sound, is that just like the light spectrum, or our sense of smell, is that humans cannot hear every sound. There are frequencies that move around us all of the time that we are oblivious to. Think of a dog whistle (the object, not how public figures try to shine up their bigotry). The high pitched tone is unique in a way that dogs’ ears can hear it, while ours cannot. Dog whistles produce very high frequency sound waves. but there are also very low frequency sound waves that are outside of our hearing range, as well. This is called infrasound (again, think infrared, the light wave frequencies below our lowest level of perception), and it is produced by many things, slowly covering vast distances with its long and low waves.

This is where Brian House comes in. House is an artist and a professor, holding a PhD in computer music, utilizing interdisciplinary research and modern technology to create internationally renowned sound exhibits that have been displayed from MoMA to Los Angeles to Stockholm and beyond, gaining recognition from WIRED, The New York Times Magazine, The Guardian, and even a listing in TIME Magazine’s Best Inventions issue. He is an assistant professor of art at Amherst College and has been published in numerous scholarly and scientific journals. His recorded output, so far, includes improvised acoustic instruments merged with field recordings, but he is on the cusp of releasing a new project on November 7th, on Gruenrekorder, entitled Everyday Infrasound In An Uncertain World that documents recorded infrasound, using devices called macrophones to record and then speeding up the recordings by a factor of 60, allowing for these novel sounds to become audible.

‘Infrasound is an anthropocentric term,’ Brian says. ‘It just means sound below the frequency range that any human can hear, typically defined as sound lower than 20 Hz. ‘Sound’ in this case is periodic vibration in the atmosphere (seismic infrasound is also a thing, but I’m only dealing with what is moving through the air).’ This in and of itself is fascinating, but Brian’s interest is much more robust and detailed than mine:

‘There are two qualities of atmospheric infrasound that I find fascinating. The first is that infrasound is not only low; it is distant. That is, these long wavelengths (like a mile long) can travel vast distances through the atmosphere—even all the way around the globe. Knowing that, I feel that hearing these sounds changes my relationship to planet as a whole. I’m not imagining that I’m looking at the globe from outer space, in some disembodied way, I’m stretching out my sense of what’s around me where I stand. The second is that atmospheric infrasound comes from sources that are at the threshold between what is anthropogenic and what is geophysical. Changing ocean currents, wildfires, turbines, receding glaciers, industrial HVACs, superstorms … this is where climate change is literally happening. And these things make noise. So at the same time that we’ve changed our sensation of the planet, we’re also witnessing what is happening.’

To capture these sounds, Brian has developed bespoke recording gear:

”Macrophones’ is my term for the instruments I’ve put together that encompass a sensor and wind-mitigation manifold. There’s been a few iterations, some focused on portability, others on low-frequency fidelity, and others on the sculptural aspect. The primary form of this project is an installation artwork where visitors can listen to the infrasound happening right where they are. While I’m looking for the right exhibition opportunity for that, I wanted to release this album, because I just found the sounds so compelling’

Everyday Infrasound in an Uncertain World is more than compelling; it is awe inspiring. The sounds slip in and out, like some mysterious interdimensional wraith cutting in and out of our shared reality in some sci-fi/horror film, but for as ominous as these sounds can be, they arrive with an immense sense of beauty and wonder, like witnessing some new, uncharted journey into somewhere we were never supposed to go. It isn’t all low rumbles, either. There are high pitched whistles and pings and fluttering warbles, but only the highest sounds on the recordings are barely audible to us in nature. Brian elaborates:

‘…the Macrophones have a sample rate of 100 Hz as well as some additional filtering, so 40 hz is about the highest frequency they capture, which is audible sound, but just barely. Single digit frequencies are the sweet spot, and it goes down to a quarter of a Hz. Speeding the recordings up by a factor of 60 raises the pitch by ~6 octaves. And I should say that that ratio is a subjective choice. To me, it made sense because it maintained the weight of these sounds while raising them just enough to be audible.’

In a way, listening to this record is like listening to a noise album: you have to let the sounds happen and surprise you. With each new sound, one cannot help but wonder where it came from. For the time being, however, identifying the sources of each sound is elusive. ‘I can say that I’ve gained some intuition about which sounds are anthropogenic and which are geophysical,’ says House, ‘But much of what is there, I have no idea where it’s coming from, and the scientists I’ve worked with have not had answers either. Part of my motivation for getting this out there is to learn more about what I’m listening to.’ Knowing those sources could help provide greater context to Earth’s cycles, environmental degradation, and man’s indifference, but Brian says, ‘the sources don’t ultimately matter to me, it’s about the aesthetics of this usually inaudible world.’

Brian House has traveled far and wide with his macrophones, yet Everyday Infrasound was recorded in Amherst, Massachusetts. Besides being Brian’s home, he adds:

‘…it is purposefully not a charismatic space—we’re talking about suburban/rural Massachusetts. I’ve also recorded on Svalbard, and in old growth forests in Oregon, etc etc. But what is remarkable to me is that infrasound is everywhere. You don’t have to be in an exotic location to capture it. It’s all one atmosphere. So I think being in Amherst helps make that point. If I said I was in Antarctica or whatever, you’d receive it very differently, and honestly I am also very tired of Western sound artists extracting sound from the global ‘elsewhere’. Wherever we are, we’re listening to the planet.’

This album seems more like a science project than what people usually think of in terms of music. ‘I want this record to be understood as documentary as opposed to composition,’ Brian says. Yet it is in this document that the art arises. Like a photographer, Brian House is changing how we understand the world around us by exposing us to perspectives we haven’t considered about how we connect with our surroundings, but ultimately what he is doing isn’t solely about the science, either. ‘My macrophones are tuned for aesthetic purposes,’ he says, adding that geologists and vulcanologists use infrasound to learn more about the seismic and structural elements of the earth while the Comprehensive Test Bad Treaty Organization uses infrasound to monitor nuclear weapons testing.I know I am still sorting out how listening to these recordings make me feel, and I am certain their impact will linger, For Brian House, the impact is more defined and profound:

‘They’ve taught me to listen in a new way. That sounds cliché, but when you’re not sure what the sound is, or even what sound is, you have to follow the lead of signal and coax it into being on its own terms. I say that in regard to the mixing and mastering process. At the end, I feel like I have an intimate relationship with all these whistles and booms, whatever they are. So, now I’m walking around the world, and I know something more is there. Everywhere. Many sound artists treat listening as a kind of sacral act, and I get that, but I’ve always been more interested in the poetics and politics of everyday life. I’m a fan of Henri Lefebvre, for instance—also, after being out with NatGeo recording lions and being at a loss with those recordings, I decided to record urban rats instead (https://brianhouse.net/works/urban_intonation/), point being, it’s not about the elsewhere, it’s about the right here. If sound is special, it’s because it’s good at making our dynamic interdependencies accessible to the senses. You can’t get out of sound. The fact of planetary, atmospheric infrasound just makes that acute.’

All of this is truly one of the most amazing things I have run across in my decades of music obsessiveness, and I feel absolutely honored to get to cover such an innovative and unique artist. Brian House isn’t letting his curiosity slow down, either. ‘I’ve been working with the astrophysicist Jeff Hazboun, who’s part of the NANOGrav project that tracks cosmic gravitational waves via pulsar triangulation,‘ he says. ‘It’s wild. What I’m interested in there is the problem of ‘groundlessness’—that is, in a universe without absolute reference points, how do we situate ourselves and act with purpose? In many ways, it’s an extension of the thinking in the Macrophones project.’Be on the lookout for more from Brian House, whether it is musical or more of a documentary; he has a knack for finding the most interesting ways to capture and manipulate sound, and maybe through that, we can all come to appreciate sound and our home planet with more empathy and grace than we have ever given it. Like the David Attenborough of sound, Brian House is leaving an unparalleled love letter to planet earth in the liminal space where science and art collide, bridging the gap between what we can witness and what we stand to lose.Check out more from Brian on his website, Instagram, and Bandcamp pages!

link