Water Beetles of Pollardstown Fen | Tom Lawrence

Gruen 087 | Digital > [order]

Audio CD > [Sold Out]

Reviews

All of the sound we hear is only a fraction of all the vibrating going on in our universe –

David Dunn

What is presented in this CD is a very alien world, a hitherto unheard aural environment that breaks with all our preconceived notions of what underwater life should sound like. All our traditional conceptions and inherent cultural conditioning are overwritten, deemed void and deleted. The work contained in this CD redefines our notions of underwater life and presents a world of alarming sophisticated communication; a myriad of signal generation, perpetuated by a plethora of intelligent species. In this booklet, Pollardstown Fen and the mechanics of insect stridulation are examined before an explanation of the contexts of the sound recordings and the methodologies employed are discussed. While every attempt at comparative analysis, spectral analysis and species identification from the known literature have been made, a certain interpretive license has been used in suggesting the meaning of the sounds recorded. Without doubt, further detailed investigations are necessary to be convinced with scientific certainty the meaning and context of each communication. Another consideration is that no mechanical devices were operating on the Fen during the period that these recordings were made. The recordings are not contaminated by any electrical interference. Other than an occasional overhead aircraft, no other sounds from above the water are present in the recordings.

Pollardstown Fen is one of the last remaining calcium-rich spring-fed post-glacial valley fens in Western Europe. Preserved by the constant flow of water from 40 springs, the fen is an alkaline marsh of around 550 acres on the northern margin of the Curragh, Co.Kildare (grid ref. N765160). An ancient landscape with a unique ecology of rare species, Pollardstown Fen is of international importance and is designated a Statutory Nature Reserve, Natural Heritage Area, Special Area of Conservation, Ramsar Site and Biogenetic Reserve. According to extant research, amongst the plethora of stridulating invertebrates that exist in the aquatic ecosystems of Pollardstown Fen, are the following water beetles and water bugs: Water Scorpion (Nepa cinerea), Greater Waterboatman (Notonecta spp.), Lesser Waterboatman (Corixa spp., Sigara spp., Hesperocorixa spp., Callicorixa spp.), Water Beetle (Acilius sulcatus), Great Diving Beetle (Dytiscus marginalis), Whirligig Beetle (Gyrinus substriatus). Each of these water insects are known to produce sound through a process called stridulation.

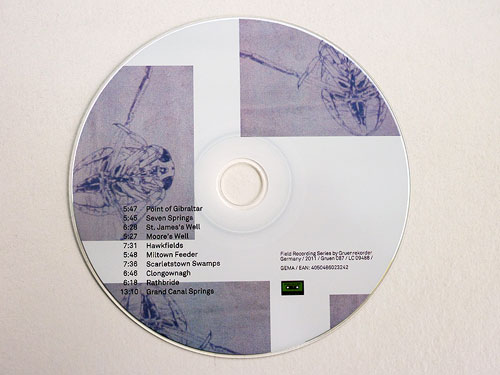

1. Point of Gibraltar / 5:47

MP3

2. Seven Springs / 5:45

3. St. James‘s Well / 6:28

MP3

4. Moore’s Well / 5:27

5. Hawkfields / 7:31

MP3

6. Miltown Feeder / 5:48

7. Scarletstown Swamps / 7:36

8. Clongownagh / 6:46

9. Rathbride / 6:18

10. Grand Canal Springs / 13:10

10 Tracks (70′46″)

CD (500 copies)

Special Thanks

The British Museum Sound Archive, School of Communications, Dublin City University, Irish National Parks and Wildlife, Chris Watson, Sarah Blunt, Mike Harding, Dr. Eugenie Regan, Stephen McCormack, Jim Cummings, Darren Smith, Prof. Nicholas Martin and Lasse-Marc Riek.

Photography Waterskater and Waterboatman by Darren Smith, Portrait by Karl Grimes.

Point of Gibraltar by Tom Lawrence.

Mastered by Mark Lorenz Kysela and Heiko Schulz.

Artwork by Flatlab | www.Flatlab.biz

Tom Lawrence is published by Touch Music (MCPS)

Field Recording Series by Gruenrekorder

Germany / 2011 / Gruen 087 / LC 09488 / GEMA / EAN: 4050486023242

Roger Batty | Musique Machine

“Water Beetles of Pollardstown Pound” is a field recording based release that journeys into the alien & mostly unheard world of aquatic insects. Tom Lawrence was a wildlife sound recordist, musician and educator, who lived in Dublin Island- sadly he passed away in late 2011, but this release is a fitting tribute to his ability to capture the strange & unique sounds of wildlife, and in particular here insects.

Pollardstown Pound, or Pollardstown Fen as it’s known locally is situated on the northern margin of the Curragh, approximately 3km from Newbridge, County Kildare in Ireland. The area of the Fen covers 220 hectares, and it’s an area of alkaline peat land that obtains its nutrients from calcium rich spring water. The site is of international importance, as these type of Fens’s are now rare in Ireland and Western Europe. In addition, it contains a number of rare vegetation types and invertebrates which include aquatic insects. Also the Fen has had an uninterrupted pollen record of the changes in the composition of its vegetation going back to the last ice age.

The CD release features in all ten tracks that last between just under the six minute mark to just over the thirteen minute mark. The release features recordings from ten separate sights on the Fen- a few of field recordings here have been slightly tampered with due to the sound level of some of the insects been inaudible to human ears, and also time compression has sometimes been used on recordings made of say a 24 hour period, but seemingly most of the sounds you hear are untouched. The recordings here were mostly done with hydrophones placed closed to the insect subjects, and apart from the odd sound of aircraft this recording features just recordings of the insects in their natural habituate.

The release features recordings of various Water Beetle & Water Bugs such as: Water Scorpion, Greater Waterboatmen, Lesser Waterboatmen, Water Beetle, Great Driving Beetle, and Whirligig Beetle. And each track features their often dense & complex sounds which take in manner of: clicking’s, wirings, croaks, reeling’s, creaking’s, jittering, purrs & high pitch chatters. The sounds of the aquatic insects are often many layered, so you’ll have for example mid to high range clicking’s against low buzzing elements. Also quite often the sounds/ calls take on a rhythmic & repetitive structure too. At times the calls/ sounds either sound like strange alien Electronica, of even dense & detailed noise composition.

The eight page booklet that comes with the album features a full write-up about the Pollardstown Fen in genreal. Then each track has it’s own small write-up as Mr Lawrence details the recording’s progresses, & the origin of each sound heard.

I can really see this release appealing out side the normal field recording market, as the sounds on offer here are quite unique, often almost rhythmic/ structured & odd appealing too. So if you enjoy unusual sound be it noise or dense/complex sounding making this is well worth a look.

Ian | Wonderful Wooden Reasons

Gruenrekorder continue their run of outstanding releases with this set of recordings made by Lawrence of the underwater denizens of Pollardstown Fen outside of Kildare in Ireland.

The recordings are unadorned and, to a great extent, unprocessed with only sounds below the levels of human hearing brought up into our range. The array of sounds on display is simply astounding. At times it’s hard to credit that such a beautiful cacophony is natural. One forgets what is playing as dada-esque sound collages reminiscent of NWW or AMM tumble past. The complexity and the richness of the totality of the sounds lends it a compositional flavour that is then made all the stronger when one snaps back to reality and fully remembers what is playing.

I’ve had this on repeat for the best part of two days now and am still finding depths and nuances I’d previously missed. Fantastic album on a fantastic label.

Lee Gardner | City Paper

The microsonic world of a collection of aquatic insects biding their scant days on this earth in the waters of an alkaline marsh in County Kildaire, Ireland.

There is a sense of building to “Point of Gibraltar,” from the first low, tectonic-sounding rumbles to a sort of sizzling static sound, punctuated by periodic oscillations, like an especially minimal pop hook. A new intermittent tone—almost like an electronic whoop or shriek, far in the distance—kicks the track into a higher key/gear, shadowed by a varying croaking sound. You can practically picture the synth operator turning a knob, or maybe pawing at a laptop touchpad lightly. At last a buzzy drone, like an old analog dial tone, ushers out the five-minute-plus cut. And thus, you have been introduced to the microsonic world of a collection of aquatic insects biding their scant days on this earth in the waters of an alkaline marsh in County Kildaire, Ireland.

Tom Lawrence, an academic, ecologist, and sound artist who died Oct. 19, acknowledges in the liner notes that he boiled the events of a 24-hour field recording down to that five-minute-ish length, and that he raised the frequency of certain sounds captured that might otherwise escape human hearing, but other than such interventions the sounds on Water Beetles of Pollardstown Fen are just that. There’s nothing electronic or, other than a little carry-over rain and thunder here and there, from the world above the surface of the water. And the sounds he captured, if not likely to supplant whatever’s happening in minimal techno or experimental drone music right now, prove a fascinating eavesdrop on the rich sonic worlds that coexist with ours, all around us.

The disc isn’t all quiet hums and bubbly burbles. “St. James’s Well” features a wheedling, almost shortwave-radio static-y call from a bug known as a waterboatman, followed by froggy croaking from a water beetle and what almost sounds like metronomic percussion from various other six-legged sources. Final track “Grand Canal Springs” culminates the disc in a collection of low-frequency rumbles and squawks from a water scorpion that sound for all the world like a chainsaw idling. This is both a varied and surprisingly regular sonic environment, at least in the sense that the sounds are often orderly in their arrangement, with rock-solid rhythms. The painstakingly recorded and exquisitely presented Water Beetles of Pollardston Fen probably constitutes background music, at best, at least after the first few listens, but the fact that it passes for music at all is a revelation.

Cheryl Tipp | Wildlife Sound Recording Society

The Autumn 2011 edition of Wildlife Sound.

‘Water Beetles of Pollardstown Fen’ is a fascinating publication that takes

the listener on an underwater journey through the heart of this ancient

waterway. Situated in the Curragh, Co. Kildare, Pollardstown is one of the

last remaining post-glacial fens of its kind in western Europe and supports a

vast array of both terrestrial and aquatic flora and fauna. The significance of

this area has led to various forms of protection and today Pollardstown Fen is

listed as a Statutory Nature Reserve, Natural Heritage Area, Special Area of

Conservation, Ramsar Site and Biogenetic Reserve.

The history and ecology of Pollardstown is worthy of an article all to itself,

but for now let’s get back to the recordings. The CD features ten tracks in

total, each of which focuses on a particular location around the fen. The

accompanying booklet provides excellent sleeve notes that explain the

various sounds that can be heard through the course of each recording and

really help when trying to visualise the scene. Tom Lawrence wrote in the

booklet introduction:

“What is presented in this CD is a very alien world, a hitherto unheard aural

environment that breaks with all our preconceived notions of what underwater

life should sound like.”

This sums up the personality of the publication perfectly. It truly is like

embarking on an adventure through some undiscovered realm where one is

overwhelmed by the plethora of unusual and unexpected sounds that come

together to form the sonic landscape.

So many weird and wonderful sounds are encountered during the course of

this listening experience that it would be impossible to explain all of them.

To give you some idea of the content however, one can expect to hear the

bubbling sounds of photosynthesizing plants, alert calls from invertebrates

such as the Great Diving Beetle (Dytiscus marginalis), Water Scorpion (Nepa

cinerea), and Whirligig Beetle (Gyrinus substriatus), and the oscillating songs

of different types of Waterboatmen. Rhythmical clicks, taps, trills and buzzes

create a totally unique atmosphere that constantly changes as individuals

come and go.

‘Water Beetles of Pollardstown Fen’ is not your average soundscape CD but

this deviation from the norm is no bad thing. As much as we all love listening

to the amazing sounds of terrestrial locations around the world, there’s

something exciting and refreshing about this voyage into the unknown. Tom

Lawrence has shared this incredible melting pot of sounds with us and I for

one am really grateful that he did.

If you haven’t already decided to buy this just ‚cause of the title (which is indeed indicative of what this is – field recordings of water beetles!!!), we suppose we should provide something of a review. Though, if you’re like us, there’s not much more you need to know besides that it’s WATER BEETLES – and a release on the great German sound-art label Gruenrekorder…

The liner notes in the cd booklet here begin with a very apt quote from composer David Dunn: „All of the sound we hear is only a fraction of all the vibrating going on in our universe“. And while it’s probably good that we can’t hear it all, all the time (boy that would be noisy) it’s also cool once in a while to experience some of the sounds that we’re usually missing out on. In this case, a sonic glimpse of another, secret world, what it would sound like if you lived in a marsh, and got your ears up close underwater next to some talkative, chit-chattering insects… which, interestingly, is a lot like some stuff in our experimental/drone section. Turns out the water beetles of Pollardstown Fen make mesmeric mad-scientist „music“ that would fit in with the clicks and cuts on Raster-Noton! Abstract, ambient, but not exactly beatless – there’s rhythmic pulses to the seeming electronic transmissions from these beetles. From track to track it’s quite varied, these tracks teeming with all manner of bleepings and burblings, chirpings and cracklings… constantly changing, constantly fascinating, the noises these waterbugs make with their microscopic mating „cries“ is AMAZING. Buzzing drones, sferic-like swoops, sawing sounds, gurgling grind, morphing and modulating in pitch… And it’s not just them, there’s other sounds found in their aquatic environment – did you know that photosynthesizing plants made sounds?

The ten tracks here, all recorded at locations within the Pollardstown Fen, an ancient alkaline marsh in County Kildare, Ireland, might somehow suggest mechanical sources, but are all indeed natural and organic (the liner notes take pains to specifically state that there’s no electrical interference to be heard here, nor were any mechanical devices in operation upon the Fen at the time of these recordings). And yes, though we are quite happy to let our imaginations make the most of these recordings without any further information, for the curious the cd booklet does contain detailed notes, getting all technical and scientific about both the recordings and the insects in question, which should convince any skeptics suspicious about the actual origin of these sounds! Let’s quote an example here, the description of track ten, just to give you the full flavor of the text, and also some idea of what you’re in for, when you listen: „This recording is a protracted performance given by a single waterbug (Water Scorpion) in heightened antagonistic stance. The hydrophone has been positioned about one inch from the insect. The insect stridulated in this way for approximately nine hours. In the background the communicative songs of the wider ecosystem can be heard. Towards the end of the recording an interesting oscillation technique takes place.“ On that track, they only let that antagonistic waterbug go on for just about 13 minutes, but the whole disc itself is well over an hour and always interesting, and for us ultimately meditative.

NATURE: The Water Boatman’s Song

BBC Radio 4, Tue 10 Jan 11.02, rpt Thur 12 Jan 21.02

Writer Paul Evans accompanies sound recordist Tom Lawrence on a journey in sound across Pollardstown Fen to hear the extraordinary sounds of an underwater orchestra of aquatic insects. Additional sound recordings: Chris Watson, Producer Sarah Blunt

framework radio | #363

phonography / field recording; contextual and decontextualized sound activity presented by patrick mcginley

another slow burn show this week with some amazing sounds from a few artists new to the show (vahram muradyan, mimosa | moize, kirill platonkin, des coulam), along with some long-time regulars (doug haire, sala, cedric anglaret). but first i feel i must pay homage to one of our new discoveries – it was several months ago that the great gruenrekorder label sent us this stunning album of underwater sounds recorded by the ireland-based artist and scholar, tom lawrence. we hadn’t encountered him before, which now seems surprising, having researched a bit his activities, and we’ve never been in direct contact with him. so it was only in the process of putting together this playlist, after the show containing tom’s sounds had aired, that we discovered the sad news that tom lawrence passed away unexpectedly in october 2011. it is clear that the recording community has lost an amazing artist, and from what we have read, a wonderful person. our thoughts are with his family and friends, and we are proud to be able to include his sounds in this edition of the show.

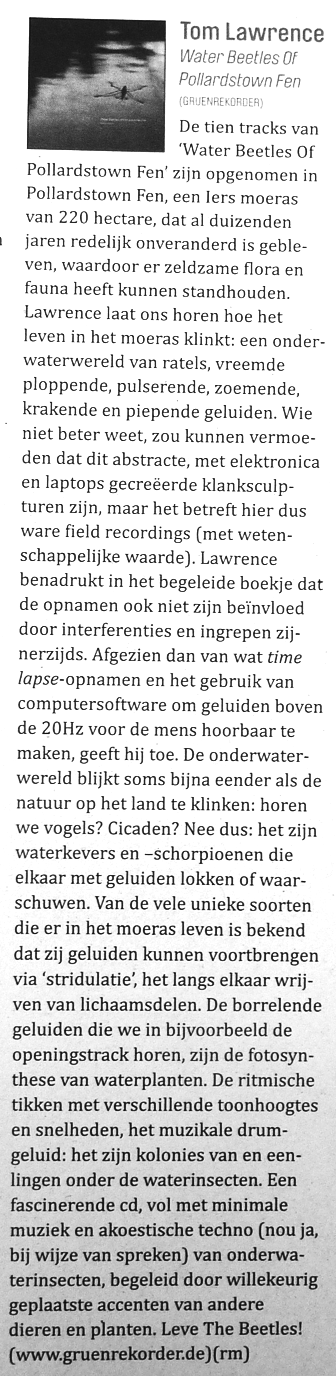

rm | Gonzo (circus) #106

Sean Cooper | Noise From the Field

Barking tree frogs, exploding dragonflies, crackling Arctic fjords—the Top 10 wildest field recordings.

[…] Pollardstown Fen is an ancient, 500-acre, spring-fed alkali marsh in County Kildare, 30 miles west of Dublin, but to listen to these hydrophone recordings by Irish musicologist Tom Lawrence, you’d think it was a well-stocked video arcade circa 1985. Electronic stabs, pulsing laser blasts, and a thick blanket of granular static made by the whirlygigs, diving beetles, and water striders skimming across the ponds’ surfaces are among the least natural-sounding nature sounds you’re ever likely to hear. To conjure them, the insects use a process called stridulation, a kind of self-frottage (think crickets) in which textured portions of the elytra and exoskeleton are rubbed, plucked, and otherwise abraded to produce sounds of varying frequency and tone. What are they saying? Beyond general speculation about mating behavior and territorial disputes, scientists aren’t sure.

DID YOU KNOW: Many of Ireland’s fens dried up to form its now ubiquitous peat bogs; Pollardstown survived thanks to a steady supply of water from an adjacent aquifer.

link

Ron Schepper | textura

Tom Lawrence brings an impressive set of credentials to his own Field Recording Series project, Water Beetles of Pollardstown Fen. A wildlife sound recordist, musician, and educator, he’s worked with directors for BBC, Disney, and The History Channel, among others, and works at the School of Communications, Dublin City University where he lectures on film music, recording practice, and sonic art and works with Max/MSP/Jitter and spectral analysis software. Like Yanagisawa’s, Lawrence’s CD captures an alien world, in this case an aquatic environment of a sonic character radically different from what most listeners will have been exposed to before. Certainly the recording makes good on the quote by David Dunn included in the acompanying booklet, “All of the sound we hear is only a fraction of all the vibrating going on in our universe,” and not many of us will presumably have spent a whole lot of time listening to water beetles. With Lawrence capturing almost all of the sounds by placing his microphone below the water surface at Pollardstown Fen, an alkaline marsh of approximately 550 acres located in Northern Ireland, his recording offers a remarkable glimpse into a part of the natural world we generally overlook, despite it being, in some sense, as close to us as the nearest country pond. Among the water beetles and water bugs captured on the CD are the Water Scorpion, Greater Waterboatman, Lesser Waterboatman, Water Beetle, Great Diving Beetle, and Whirligig Beetle, each of whom generates sound through a process called stridulation, that is, the rubbing together of certain body parts.

Water Beetles of Pollardstown Fen opens with a time-lapse setting called “Point of Gibraltar” that Lawrence edited down from twenty-fours to the six-minute setting heard on the recording in order to reveal to the listener the subterranean world existing below the fen. Using computer software, he was able to capture sounds below the range of human hearing. The mating calls of Water Beetles and the clicking of the Great Diving Beetle are just two of the sounds that appear amidst the teeming sonic activity documented by Lawrence. The warbling cries of Water Beetles introduce “Seven Springs” and are then joined by the ammo-like firing of other bugs‘ calls, while an autumn storm of thunder and drizzle segues into the spiraling song of a Waterboatman during “St. James’s Well.” Perhaps the disc’s most representative track is “Hawkfields,” as it includes a broad range of sounds from a variety of types, with the incessant crackle of a Great Diving Beetle’s martial drumming, the singing of Water Beetles, and the calls of a community of Whirligig Beetles among the variety on display. “Grand Canal Springs” takes the project concept to its furthest extreme and, admittedly, may prove taxing for even the most devoted listener. We hear the stridulating sound of a single waterbug, the Water Scorpion (the hydrophone positioned one inch away from the insect) for thirteen minutes—though the insect—in a “heightened antagonistic stance,” Lawrence informs us—stridulated in this way for a full nine hours.

Like Yanagisawa’s recording, Lawrence’s material often brings in unrelated associations, such as when the Water Beetle calls in “Moore’s Well” suggest the revving of a motorcycle engine. “Clongownagh,” on the other hand, at times could pass for a decades-old field recording capturing on tape the drumming and calls of a newly discovered tribe in the African jungle along with assorted wildlife sounds as the backdrop. Be forewarned: Lawrence’s disc is as uncompromising as fields-recordings releases get, and seventy minutes of material of this type is a lot—it’s not for the impatient, in other words. There’s no question, though, that the world Lawrence has documented is a fascinating and incredibly rich one.

link

Chris Whitehead | The Field Reporter

Stridulate: (Of an insect) to make a shrill sound by rubbing wings, legs or other body parts together.

As any sound recordist knows, dropping a hydrophone into a body of water crosses a threshold. A barrier is broken between our world and an alien realm that exists alongside it. Bubbles rising from underwater plants become radar blips. Unfathomable clicks and pulses emanate from the unseen inhabitants of a veiled world.

For this recording Dublin based acoustic ecologist and sound artist Tom Lawrence has documented the stridulations of the insect population of Pollardstown Fen, a 235 hectare area of peatland fed by calcium rich streams in County Kildaire, Ireland. The effect is of listening to broadcasts of unknown code. Invertebrate morse communications sent out into the submarine ether.

At times curiously reminiscent of the minimal electronic work of Ryoji Ikeda (+/- etc), there is a necessarily limited sound palate to these pieces. Yet the mystery of why this activity takes place adds an intriguing aura to the act of listening. Eavesdropping on Great Diving Beetles and Water Scorpions whose motives can only be guessed at. Any attempt to interpret meaning and context from these intentionally produced sounds must be tentative lest we fall victim to anthropomorphism.

Although divided into 10 tracks reflecting different environments in the fen, the work plays beautifully as a whole. Possessed of a certain scientific rigour, the well written accompanying text details each location, its vegetation and topography, and of course the insect residents which live there.

There has been mention in The Field Reporter of the whys and wherefores of detailing sound sources. Tom Lawrence’s recordings are a perfect example of how the attribution of a sound to its creator and location can enhance the experience for the listener. The fact that these songs are made by communities of tiny arthropods in a normally closed off realm cannot help but instil a sense of wonder.

The decision to provide additional written information alongside any recording is the individual artist’s, and should therefore in my opinion be considered as part of the work as a totality, together with any images or other material. There is always the option of not reading the track descriptions. The decision to do so or not is clearly the listener’s.

The final track is a study of a Water Scorpion stridulating into a hydrophone placed about 1 inch away. The piece lasts 13 minutes and is the longest of the tracks on the CD, yet the insect’s performance actually lasted approximately nine hours. A full working day. Impossible to fathom.

Nick Cain | The Wire – Issue: #332

Recently there has been an upsurge in the use of field recordings by a range of practitioners. One of its most vexing traits is the frequency with which the recordings are treated to fit the requirements of an existing vocabulary, whether it be Noise, drone or electroacoustic Improv, draining them of locality or character. German imprint Gruenrekorder’s Field Recordings series offers a haven of site-specificity. The label also runs Soundscapes and Sound Art lines, whose releases subject field recordings to various compositional or conceptual strategies. The 30 or so Field Recordings CDs mostly contain unprocessed location recordings. The results can be hit or miss, but this pair of discs are two of the series’s more rewarding entries. Eisuke Yanagisawa’s Ultrasonic Scapes collects ten recordings of ultrasonic (beyond human audio perception) sounds, made mostly in Kyoto with the help of a bat detector, and presents them untreated save for slight amplification. There are a couple of nature recordings: bat calls (unfurling patterns of click-tones), and a noisy cicada chorus. But mostly Yanagisawa is interested in listening to the hidden sounds of electronic devices and urban public spaces. White noise frequencies are ever-present, flecked with granular detail (presumably a by-product of the technology used). Elsewhere sounds cohere into repetitive patterns: the dull grinding of a street light, the rhythmic click of an automatic gate, or the hum of a TV. There’s a delightful series of tonal tinkles and pings in “Furin”. But most of them are almost comforting for the degree of structure they reveal – a kind of mundanity in the imperceptible.

UK recordist Tom Lawrence finds similar certainties in a very different environment. Water Beetles… is a collection of underwater recordings from a 550 acre untouched marsh in Co Kildare, Ireland. In his notes Lawrence explains the historical and geographical context for each of the tracks, as well as the compositional processes he’s used – mostly simple montage or timelapse editing, blending different recordings from the same location with great sensitivity. The sounds he uncovers are often repetitive or constant – the klaxon buzzings of water beetle stridulations; the beat-pulsing frequency of a corixid water bug’s song; the clacking rhythms of a whirligig beetle’s alert call – yet all are fascinating for the detail they reveal about this submerged world. Lawrence’s respect for the sonic richness and narrative integrity of his chosen environment is palpable.

Dan Warburton | PARIS Transatlantic Magazine

To quote acoustic ecologist David Dunn (who certainly knows what he’s talking about): „All of the sound we hear is only a fraction of all the vibrating going on in our universe.“ Well, there’s certainly a hell of a lot of vibrating going on in these ten tracks, and it started thousands of years before Tom Lawrence took his hydrophones into Pollardstown Fen, a 550-acre alkaline post-glacial fen in County Kildare, Ireland. As the album title makes clear, most of these amazing sounds are produced by insects rubbing bits of their bodies together – „stridulation“ sounds better – and Lawrence had to sit heroically through hours of thunderstorms to record it („this song was actually recorded at the end of an eight-hour stridulation“). As you might expect, the eight-page booklet provides not only precise details regarding the recordings, but also background historical information and long lists of local fauna, though you don’t have to know that the area is home to Pugsley’s Marsh Orchid to appreciate the music. I’ll stick with the word „music“ too, if you don’t mind – if you’d played me parts of this (the end of track three, for example) and told me in advance that it was a live electronic sound sculpture by David Tudor, I wouldn’t have been at all surprised. In fact, I’m in two minds about the excessive documentation that seems to be a prerequisite of field recordings (and a Gruenrekorder speciality): sure, it’s fascinating to learn that these extraordinarily weird gurgles, buzzes and bleeps are produced by those little beasties I used to fish out of the Rochdale Canal as a kid (I fished out plenty of old shoes, rusting bicycle parts and used condoms too), but being able to visualise the little critter somehow detracts from the magic of the sounds it makes. Here’s hoping you managed to listen to this before reading the notes accompanying it. And this review.

Ed Pinsent | The Sound Projector

Beetles For Sale

The German label Gruenrekorder is of course home to many fine examples of field recordings and related sound art, but this new one by Tom Lawrence ought to win some sort of award from whatever papal body or other officiating body in Western Christendom decides such matters. Water Beetles of Pollardstown Fen (GRUEN 087) is an ambitious, meticulously documented and radical work, which aims to set high standards in this area and at the same time reveal new aspects to the hidden worlds of underwater life. Lawrence presents, in stark documentary style, numerous communication systems taking place among insect life, and provides detailed notes with his interpretations and analysis of what these sounds mean. 70 minutes, ten recordings – compressed down from much lengthier periods of recording, study and research. Lawrence aims to create something that “breaks with all our preconceived notions of what underwater life should sound like”, and has received support from various archival bodies, educational institutions and national parks, as well as noted individual practitioners in the field (Chris Watson among them, natch). Even the chosen site of study is important from an ecological and conservational standpoint, and these areas too are well understood by Lawrence. Of course I know next to zero about entomology or any of the other subjects mentioned above, so can’t really assess the deeper value of the man’s work here, but I sense this release will represent a benchmark of achievement in the genre of field recording, to say nothing of the ideas that are packed into these pages of notes. Might I also add that the disc sounds absolutely fantastic and I can’t recommend it enough – it is a total triumph.

Guillermo Escudero | LOOP

Tom Lawrence is a sound recordist, musician and educator. Tom works at School of Communications, Dublin City University where he is a lecturer in film music, recording practice and sonic art.

This CD contains recordings made in the Pollardstown Fen which is a National Nature Reserve since 1986. It is also a Special Area of Conservation, located in Northern Ireland. Lawrence research the underwater insects that live in this reserve that are known to produce sound through a process called stridulation (is the act of producing sound by rubbing together certain body parts. This behavior is mostly associated with insects).

In the recordings also was registered the sound of streams of water, rain and storm.

Lawrence creates an amazing wildlife natural sound that modern human beings are not conscious at all. This is a good way to recognize also the sound that could be around us.

Zipo | aufabwegen

Es ist fast unglaublich, dass diese Klänge unbearbeitet sein sollen: Die Wasserläufer aus dem Bioreservat Pollardstwon Fen in Irland machen eine spektakuläre Noisemusik. Von kruschelndem Whitenoise Gebrutzel über acidmäßige Fieps- und Sirenentöne ist hier das ganze Klangarsenal der Industrial-Szene vertreten, aber in echt! Die CD von Tom Lawrence, liebevoll mit Texten dokumentiert, ist wieder mal ein Fall von: die Schönheit ist um uns herum, wir müssen sie nur erkennen. Diese Erkenntnis kommt mir, während ich in einem düsteren Zimmer hocke vor einem elektronischen Gerät dessen Kühlung grau brummt und dessen Bildschirmflimmern mit Kopfschmerzen macht. Dabei könnte ich draußen am Kanal sein und den Entchen und Wassermücken lauschen…

The Silent Ballet staff | The Silent Ballet

Release of the Month – July – 2011

The Silent Ballet staff counts down its top picks of the month.

In Simon Reynolds‘ recently released Retromania, the columnist makes a strong case for the theory that today’s music is hopelessly enamored with that of the past. In the arena of popular music, he’s entirely correct; the hits of today blithely follow the template of the past two decades, and it’s been a while since a new genre (such as rock, disco or rap) has taken the world by storm.

For the most part, musicians do look to the past for inspiration, and every „new“ genre blends elements of the old. Foreign sounds take time to feel familiar, which is why innovation is typically found on the fringes; by the time the mainstream catches up, the outskirts have moved on. But when it comes to creativity, there’s no reason to despair. New sounds continue to grow in the crevasses.

In the past month alone, we’ve seen the release of albums that amplify the sounds of water beetles and abandoned malls; an album performed on broken harmoniums; a debut EP presented in a box of beach glass; and a concert event preserved on a flash drive hidden in a pocket-sized tiger.* This is an extremely exciting time for music, if one knows where to look.

This month’s top picks may build upon the past, but none can be considered „retro“; each is clearly a 21st century creation. This is where the future of music finds its foundation: not on the airwaves, not in the adverts, but here in the field of lawless sonics, the teeming desert beyond the flourescent lights.

* Tom Lawrence’s Water Beetles of Pollardtown Fen; Simon Whetham’s Mall Muzak; Sigbjorn Apeland’s Glossolalia; sink/sink’s center folds; Eleven Tigers‘ 111.

Frans de Waard | VITAL WEEKLY

Gruenrekorder always knows where to find new people involved in the world of field recordings. Here its one Tom Lawrence, who created a CD with ten different pieces all recorded at the Pollardstown Fen, ‚one of the last remaining calcium-rich spring-fed post-glacial valley fens in Western Europe‘. Sticking his microphone mostly below the water level, he picks up animal life, water beetles and water bugs and such like. Amazing stuff! The singing of the beetles, as captured in ‚Seven Springs‘ sound great. There is no ‚treatment‘, such a fine capture of events, the pure phonography of an environment. Not an easy place to access, with all these nervous sounds, soft high end peeps and the hectic life of so many small creatures. At many times things sound quite mechanical, like lo-fi objects buzzing and rotating. Each of the pieces is well documented. Quite a captivating release, but one that requires total concentration: the first time I played it, I wasn’t paying attention and it irritated the hell out of me. […]

Michael Viney | The Irish Times

ANOTHER LIFE: CREATING OUR garden pond some 25 years ago, I blanketed the raw black plastic of its floor with a layer of earth and sowed this with roots of water plants dug out of lakes behind the shore. This rash and probably illicit strategy did, indeed, furnish the pond agreeably with rapid vegetation – bogbean, water mint, mare’s tail and the rest.

It also skipped a few stages in the natural ambition of ponds to fill themselves in with decaying leaves and stems. Today, tiring in my old age of dragging superfluous biomass out of the pond each autumn, I have settled for succession to a bean-shaped fen which, left alone, might even end up as a miniature raised bog.

For a few years, however, there was still enough open water to serve the annual multitude of mating frogs and encourage soothing meditations on the antics of aquatic insects. On the surface, pond skaters dimpled the skin of the water and whirligig beetles spun in circles of shiny ballbearings. Below, great diving beetles glided through sun and shadow in pursuit of tadpoles and water boatmen rowed up and down for necessary refills of air. All this was played out in a distant, subaqueous silence, while birdsong and bumblebees strummed around my ears.

To discover the underwater sounds of the insect world – to realise they exist at all – is a mind-blowing event in one’s sharing with nature, rather like hearing whalesong for the very first time or seeing Earth from space. For that I have to thank Dr Tom Lawrence, lecturer in sound and music at Dublin City University, acoustic ecologist and brilliant wildlife sound recordist.

Two years ago, he spent six months capturing the sounds of Lough Neagh, above and below the waves, for a BBC Radio 4 natural history programme. One morning he happened to catch the sounds of corixids – lesser water boatmen – stridulating underwater (I’ll come to that). It planted a seed of deep interest in the aquatic communication of invertebrates.

This led him to the ancient wetland on the northern flank of the Curragh in Co Kildare, where thousands of hours of hydrophone recordings have now been distilled into a 70-minute CD, Water Beetles of Pollardstown Fen*. Dr Lawrence calls it “a representative sonic ontology, a phonographic document of natural history”. Less formally, he talks affectionately of the “mini-moogs” whose synthesiser-like repertoire has filled him with frequent astonishment.

The first time he dropped his hydrophone into one of the drains that feed the lake at Pollardstown, his equipment overloaded with sound. Suspecting a fault, he tested circuits, changed his mixer and fitted new cables, only to find the caco- phony still there. Only when its volume wound down and “a beautiful song” emerged, did he realise it came from a colony of whirligigs he’d disturbed at the bottom of the drain.

The recordings, with great aural presence and atmosphere, are hypnotically alien, an endlessly varying chorus of clicks, chirrup- ings, churrs, buzzes and whines, pulsating and oscillating and sometimes of startling volume (like a sudden car alarm). Individual performances go on for many hours. For the water scorpion, Nepa cinerea, at the fen’s Grand Canal springs, the hydrophone was set about one inch from the insect. It kept up an angry, oscillating rasp, sometimes of 110 decibels, for nine hours. The disc samples 13 minutes of it, amid the exhalations of plants and discourse of other invertebrates.

Each of the insects is stridulating, a term more familiar from the terrestrial world of grasshoppers and crickets. In these, the penetrating, churring sound comes typically from rubbing a series of pegs on the legs across a stiff vein on a wing. In most water boatmen, a group of teeth on the front legs is rubbed against a ridge on the side of its head. This can also interact with air bubbles stored in the insect’s body to create a “song” at frequencies that sets up a sympathetic resonance in a partner.

Last month, scientists from France and Scotland reported on sounds made by Micronecta scholtzi, a water boatman just 2mm long (and not yet found among Irish species). The pulses reached at average of 78.9 decibels, making the insect, relative to size, the loudest animal on Earth. But what also drew headlines was its manner of noise- making – rubbing a ridge on its penis across ridges on its abdomen.

That does seem to match the motivation usually accorded to water beetles and bugs – competition in attracting a mate. But research suggests stridulation serves far wider purposes, as yet almost unexplored. In redefining our notions of underwater life, says Tom Lawrence, his CD “presents a world of alarming, sophisticated communication: a myriad of signal generation perpetuated by a plethora of intelligent species”. That might be pushing it a bit, but the nuanced alertness, alarm or aggression in some of the Pollardstown “voices” seems unmistakeable.

Brian Olewnick | The Bird Cage

Every so often, more so in recent years, a release passes across my desk and through my ears whose contents consist of unadulterated, unprocessed field recordings. Now, I have, I daresay, hundreds of recordings that utilize field recordings to one extent or another but even those wherein the entire contents are sounds picked up by a mic left out in the desert or beside a highway or within the hull of an old boat generally involve some degree of manipulation by the person involved, some sculpting, some design element. These can, in the right hands, be extraordinarily beautiful documents. I’m thinking of Toshiya Tsunoda’s „Scenery of Decalcomania“, for example. The choices he makes, the weight he assigns to the various elements work to create a composition which seems for all the world to be „just“ a recording of a scene but, in fact, is an idealized situation, a fictional world more incisively etched than what you’re likely to hear yourself, as a blank wall by Vermeer contains more in it than you’re likely to see, looking straight into one.

Tom Lawrence’s „Water Beetles of Pollardstown Fen“ (Gruenrekorder) is a set of ten recordings of just that, as well as a good deal of plant life. All of the sounds–and there’s an impressive variety of them–were recorded beneath the surface of the water, the mic often positioned quite close to the stridulating insect. The sounds are reasonably fascinating–how could they not be?–all clicks and whirs and guttural buzzes and whines, sometimes possessing an eerily human quality, like a covey of muttering old crones or some guy iterating a brief, pained cry. It’s certainly a world unobtainable by ones even were one to immerse head in fen so there’s a certain value having been exposed to it as all. The question is, is that value one of a purely educational or scientific sort and, if so, how to deal with it when presented as „art“. There’s also the issue, beautifully recorded though it may be, of how much is lost hearing these sounds issue from two speakers; if nothing else, the reality is a surround-sound experience. How to evaluate? Try as I might, I can’t really rate this water scorpion’s croak over that Great Diving Beetle. No reason to, of course, but after a listen or perhaps two, what does one derive from this. I now have some idea of what the insect life in this fen and, by extension, other small bodies of water, may tend to sound like which is all well and good, but am I going to go back to this to refresh my memory? In all likelihood, no. Unlike the example given above, the Tsunoda, I don’t think there will be layers to continue to peel away, relationships to discover for the simple reason that there’s not a human decision maker, at least not one making decisions of much import aside from track length. Or perhaps decisions were in fact made and the hand that made them lies a bit heavy, smoothing the sounds into a kind of sheet that, for all its wealth of sounds, carries with it a kind of sameness, a sameness that I very much doubt would be heard in situ, where one would be making his/her own decisions on how to listen, on how to balance the rich, subaqueous sound world. Somehow, something essential seems lost in the translation to disc, more so than is, of course, always the case with music transferal generally.

[…]

This is not to say that either recording isn’t worth listening to. They are, in a way (The Yanagisawa more so than the Lawrence, to these ears), even if they leave me with an extremely unsatisfied sensation. They both succeed, as near as I can do, with doing what they set out to and do so admirably and attractively but I can’t shake the feeling that I’d rather dip my ear in a pond or press it up against a street lamp myself.

Richard Pinnell | The Watchful Ear

Tonight a CD that perhaps doesn’t really fit the mood I have cultivated today from my gallery trip and reading on the train in and out of London, but as I am trying to work my way through the backlog of CD in some kind of organised fashion, and because this is the disc I have been listening to over recent days its the one I am writing about!

The CD then is a set of field recordings, if indeed field recordings is the correct description here, made in and around the Pollardstown Fen body of water in Co. Kildare, Ireland. The album is named Water Beetles of Pollardstown Fen and is by Tom Lawrence, released on the Gruenrekorder label. The ten tracks here then each portray the amazing sounds made by beetles, other insects, and assorted pondlife, much of it vegetative found in this kind of area. Now a good few years back I was lucky enough to go to a semi-stagnant pool up in Derbyshire with a few others to hear Lee Patterson drop a home made hydrophone into the water so we could hear the incredible set of sounds made by insects as they carry out something known as stridulation, which I believe is the act of rubbing together various body parts, often the back legs to create vibrations and sounds much louder than something so small should in theory be able to make. The sounds then are like buzzing synthesiser groans, or early computer game sound effects, often rhythmic yet remarkably uniform and consistent. The recordings here mostly capture these sounds as different creatures, and in some places bubbling, fizzing plantlife are recorded going about their daily, hidden, and somewhat noisy lives.

Now the sounds here are fascinating, and very well recorded. I don’t have any recordings of Lee Patterson’s work in this area so I can’t really compare it to anything, but it feels very cleanly recorded, with the sounds mostly uninterrupted, and when they are, its by thunder, or rain on the water, or other natural impacts that enhance the recordings rather than spoil them. It is impressive to hear this hidden world in all its glory, to share in the insectual conversations (are they conversations?) that are usually out of the reach of the human ear. For those that have not heard anything in this particular area before, but have an interest in field recording this CD will probably be a real ear-opener, as I remember how I felt when I was first made aware of the rich catalogue of sounds to be found under the water’s surface. The problem though, is once you have heard the sound, once the surprise is over, this CD essentially becomes a piece of nature documentation, a catalogue of amazing sounds brought to the human ear, but perhaps not really music, or rather, not really music of any great purpose or conceptual weight.

This isn’t a criticism at all, but this album falls, for me anyway, into the category of natural documentation as much as it does creative music. Aside from some tastefully simple crossfades there isn’t any editing, enhancements or attempts to sculpt these recordings into anything more than the remarkable audio photographs that they are. Subsequently then, my connection with these recordings becomes one of technical awe and natural wonder perhaps rather than one of emotional or engaged response. I don’t want to seem to be dogmatic about my response to field recordings, requiring direct input from the composer, or needing the recordings to be treated in some way, as this isn’t the case- I can enjoy listening to something like this as well as the next guy, but I do think I would prefer these sounds more if they were subsequently taken and applied to something more directly creative, composed, interacted with by a human hand/mind. Of course when a CD like this is put together, and longer tracks are cut up, decisions are made over which piece should sit beside which other piece, where a track should fade in and out there is plenty of compositional intervention taking place, but ultimately this CD sounds to me like an audio scrapbook of fascinating sounds more than it does sound like any kind of statement from Tom Lawrence. Again, this needn’t be a criticism, and I guess that if I had not heard these kinds of sounds before then I would be far more excited about hearing them here for the first time, but as I listen to the bugs chirruping and buzzing away again for the third time through tonight I can’t help but wonder what could be done with these sounds if placed into the hands of a strong compositional mind.

maeror3 | REGENERATOR

Для кого-то – просто болото, а для кого-то – уникальная экосистема. Поллардстоуновское известковое болото раскинулось на 220 гектарах по территории Ирландского графства Килдэр и зарекомендовало себя в глазах ученых как место обитания множества уникальных насекомых и растений. И пока ботаники и энтомологи изучают образцы в лабораториях, Том Лоуренс решил запечатлеть для потомков (ибо экосистема экосистемой, но бурный рост промышленности со всеми вытекающими последствиями никто не отменял) «голоса» основных обитателей болота в их естественной среде обитания – водных жуков, коих насчитывается множество видов, и каждый из них имеет свой «голос».

Бывают релизы, читать и рассматривать буклет которых гораздо интереснее, чем, слушать сам диск. Здесь мы тоже имеем дело с обстоятельным рассказом о сложном процессе подбора исходного материала – каждая композиция дополнена историей о том, в каких условиях и местах Лоуренс сутками напролет записывал еле уловимый стрекот, шуршания и прочие малоописуемые звуки, издаваемые насекомыми, чтобы потом извлечь из потока нераспознаваемые порой человеческим ухом децибелы, усилить их, свести несколько дорожек в наполненные жизнью композиции, открывающие ворота в микромир. Результатом деятельности Тома стали не просто беспристрастные «голоса живой природы» – его кропотливая работа вылилась в электроакустические пьесы, в которых преобразования исходных звуков выводят идею альбома на новый уровень, заставляют вслушиваться в детали и впадать в гипнотический ступор под напором звуковых волн от громкого монотонного стрекота, на который накладывается шум воды, шуршание травы, гул ветра и крики птиц. «Water Beetles of Pollardstown Fen» – это не беспристрастная фиксация, пригодная для музея естественных наук или для звуковых библиотек, но не подходящая для внимательного прослушивания. У автора свое видение процесса, свой подход к комбинированию звуков, свое мнение насчет полевых записей и их звучания. Поэтому, даже если вам жуки-плавунцы в принципе безразличны, но идеи «конкретной музыки» вызывают интерес, не поленитесь, поищите этот диск. Тот случай, когда слушать не менее интересно, чем читать сопроводительные тексты.

Mark Wharton | IDWAL FISHER

The worst thing about the relapse [or the ‘Istanbul Goat Virus Round Two’ as its known round these parts] is that it robbed me of my powers of concentration. During the first phase of its manifestation two weeks ago all I needed was the strength to pull a CD from its sleeve and insert it into the stereo. During the more virulent second phase all I could manage was staring out of the window whilst listening to the cricket updates on Five Live Sports Extra. As I slipped between coma and semi coma news of wickets falling in Somerset and Warickshire entered my head only to leave again moments later. As a means of whiling away the days it was as good as it was going to get. For some strange reason the sound of any kind of music drove me to absolute torment. I decided it was best left alone. These last few days then have given me some idea of what my retirement days might be like and if I ever make there in such lousy shape I may as well take up alcohol as a distraction.

Thankfully I’d become familiar with this batch of Gruenrekorder releases the first time around so it was a just a matter of working my way back in.

Gruenrekorder is a two man label stroke organisation dedicated to the promotion of experimental music and phonography. Phonography meaning ‘an acoustic experience loaden with musical sounds’. Now I’ve always been a bit of a passenger when its come to Field Recordings [a term that Gruenrekorder also use], I do have some of Chris Watson’s work, some Touch releases that cover the same ground and the odd bit by various Schimpfluch members where they’ve stuck microphones hither and thither and recorded whatever’s emerged, but this is my first serious chance to get to grips with a label dedicated to such material and to give it a serious appraisal.

[…]

Pollardstown Fen is a calcium rich, spring fed fen in Ireland which has become home to all manner of wildlife including numerous species of water beetles. Tom Lawrence took his underwater microphone there and recorded what happened beneath the surface. Apparently water beetles like to stridulate. Stridulation being the ability to announce ones presence by the rubbing one body part against another. Remarkably Lawrence recorded one particular water scorpion going at it for over nine hours at an incredible 110 decibels. Part of that experience is included here. My problem with Lawrence’s work here is that even though I find it all absolutely fascinating [ and the sleeve notes help a lot] the sounds eventually become grating and with over seventy minutes of it to go at its an arduous task. But you don’t have to play it all at once. Taken in small doses the delights of water beetles rubbing their nether regions together do reward the inquisitive listener. Track two ‘Seven Springs’ is a cacophony of several beetle species all in ‘antagonistic high alert’ the results of which are comparable to electronically produced noise albeit, one of an especially repetitive nature. Think scratched Hecker CD. Interesting material just very, very demanding on the listener.

[…]

Gruenrekorder don’t just release Field Recordings and Sound Art though, you’ll find them investigating Soundscapes as well as running a workshop and an intermittent dual language downloadable PDF magazine called Field Notes. Its archived and worthy of your attention. Theres also a few more free downloadable albums beside the one I mentioned. Having never heard of Gruenrekorder a month ago I know find myself a fervant fan.

What interests me now is has anyone done any true ‘Industrial’ field recordings? I mean in actual working factories? I’ve been musing this for the last few days. I wonder if there are too many obstacles involved? Its not like you can just turn up at a factory with your equipment and say ‘I’d to record your machines please’. First you’d have to find out which machines makes the most interesting noises and that in itself would take months of ground work. Then you’d have to get the companies permission. The company involved would no doubt have to give you assistance as I’d doubt whether they’d just let you wander around their premises until you found what you wanted. The results could be interesting, just hard to collate.

Gruenrekorder (Tom Lawrence, James Wyness, Terje Paulsen & Ákos Garai, Eisuke Yanagisawa, Ernst Karel) mentioned @ The Field Reporter / 2011 Final Report

A few words by The Field Reporter Editor Alan Smithee plus PART I of the lists with the most relevant works of 2011 made by our staff and other artists, curators and journalists.

FLAC