Ultrasonic Scapes | Eisuke Yanagisawa

Gr 081 | Gruen CD-R | Silver > [Sold Out]

MP3 & FLAC > [order]

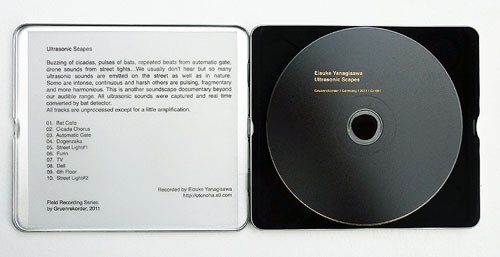

Buzzing of cicadas, pulses of bats, repeated beats from automatic gate, drone sounds from street lights…We usually don’t hear but so many ultrasonic sounds are emitted on the street as well as in nature. Some are intense, continuous and harsh others are pulsing, fragmentary and more harmonious. This is another soundscape documentary beyond our audible range. All ultrasonic sounds were captured and real time converted by bat detector. All tracks are unprocessed except for a little amplification.

1. Bat Calls

Ultrasonic echolocation calls from bats under the Sanjo Ohashi (bridge).

Recorded on August 2008, Kyoto, Japan.

2. Cicada Chorus

Cicada chorus goes far beyond the human audible range. In summer, we can hear many different varieties of cicada chorus. The sounds are so intense, full of energy for attracting females.

Recorded on August 2008, Kyoto, Japan.

3. Automatic Gate

Ultrasonic beats from automatic gate of the parking lot. It usually emits strong and repeated signals.

Recorded on August 2008, Kyoto, Japan.

4. Dogenzaka

Dogenzaka is a crowded street with lots of shops and hotels in Shibuya. Noticeable ultrasonic sounds are jangling sounds of accessories and keys as people walk down the street.

Recorded on June 2010, Tokyo, Japan.

5. Street Light#1

Street lights and illuminations of stores are the sound sources which create ultrasonic drone. I can hear the sounds as if a few frogs were calling while floating in the drone river.

Recorded on August 2008, Gion Shijo, Kyoto, Japan.

6. Furin

Furin Bells are Japanese traditional wind chimes hung under eaves. We enjoy coolness listening to the delicate sounds. I recorded in front of a souvenir shop in Sanjo.

Recorded on August 2008, Kyoto, Japan.

7. TV

I tuned in to 30 kHz of my bat detector and recorded the ultrasonic noise of my CRT-based TV in my room.

Recorded on April 2009, Kyoto, Japan.

8. Dell

Internal sounds of my dell note PC which turned out to emit strong ultrasonic noise.

Recorded on April 2009, Kyoto, Japan.

9. 6th Floor

Recorded at the 6Th floor of a department store near Shijo Station.

Recorded on July 2005, Kyoto, Japan.

10. Street Light#2

Low pitch drone sounds compared to track 5.

Recorded on August 2008, Gion Shijo, Kyoto, Japan.

10 Tracks (35′06″)

CD-R (50 copies)

Recorded by Eisuke Yanagisawa.

http://otonoha.x0.com

Some of the images taken from my video work „UltrasonicScapes (2008)“

Field Recording Series by Gruenrekorder

Gruenrekorder / Germany / 2011 / Gr 081 / LC 09488

Paperback by Salomé Voegelin, pp.165-167

Sonic Possible Worlds: Hearing the Continuum of Sound

Eisuke Yanagisawa’s recording of ultrasonic landscapes are not beautiful or particularly harmonious: they clip and grate, flange and crackle, whizz and hum, sounding more like scrambled signals than a soundscape, and yet they intrigue through what they hint at and make us hear between what actually sounds and our auditory imagination.

The ultrasonic recorder modifies frequencies beyond our hearing range into audible material, translating between an audible and an inaudible world, and granting access from one into the other—adding the unheard to what is audible and making the two compossible. These recordings present the inaudible as a variant of the same world and thus expand the threshold of its actuality and possibility into the invisible depth of the unheard—the impossible.

The first track of the album is of bats calling, presumably in crepuscular woods, evoking the sighting of all sorts of other creatures, real and mystical, that might live here in actuality or in possibility, and that might be heard if only we had the right device to shift their frequency within our range. The opportunity to hear this inaudible, impossible sound, invites the imagination of a host of other sounds emerging from the darkness to appear between the trees and shrubs and thicken the agency of a seemingly still landscape.

The bats’ calls serve as a portal into another world, a possible impossible world, whose impossibility is determined not by their nonexistence but by our physiology. Their clicking is the natural partner of Kubisch’s electromagnetic whirr and hints at a primordiality of other worlds that live as slices of this world in the inaccessible shade of the visible and the audible, and yet impact on what we perceive.

Kubisch’s whirr is manmade, an addition to the soundscape through our economical and scientific activity and reflecting on it. The bats’ call sounds independent of us and opens a world beyond human organization: a wilderness at the verge of our actual and possible worlds. It also precedes us and thus does hint not only at a contemporary inaudible but also at past inaudibility, things that might have lived and sounded here but that have now ceased to do so, and we will never know about their sounds or how to call them. These are the sounds of a post-humanist or indeed a pre-humanist world that reveal the Gothic souls of animate and inanimate objects and make us rethink the trajectory of descriptive referencing, which we adopted through an idealist philosophy chosen over a contingent and contextual naming that produces not an analytical but a phenomenological logic.

Of course, we know that bats exist and that they use ultrasound to find their way in the dark, but the rational understanding of this zoological fact does not thicken and mobilize the woods at night. The ultrasonic recorder grants entry into this other world, and invites us to add it to the slices we know about and consider actual or possible; it gives them a deeper depth and a darker groundlessness—and so when next I step into the semi-darkness of the early evening light, between trees and ferns, I will sense the agitation and mobility that composes my view.

Yanagisawa’s bat recorder renders the inaudible audible not to get me to one inaudible as a mere curiosity, but to open myself to the possibility of many impossibilities: to tune my sense to what I do not hear; to make me think of all the slices of actuality that are possible but remain impossible in a zoological, structural, archeological, and so forth, description, but which need to be heard in order to name, to gain and share access to them nevertheless.

To talk about the inaudible serves not to create a structural reference for the possible impossible, but to gain access to it, and to share those invisible points of access at the verge of possibility, not to finalize the unheard but to make it count. I do not want a scientific, aesthetic, or ideal descriptive reference of the inaudible but need to engage in its processes and materialities to name, dename, and rename what I think might sound but that I do not yet hear, to make you listen out for it also. For this purpose we need a language that emerges from listening rather than words that restrict what can be heard. This language needs to be part of the listening practice and share in its generative sensibility to produce words, the material of language, in response to the material of sound, and embrace the possible world of the audible and seek to make accessible also a sonic possible impossible world from the invisible actions of its inaudible things. Such a language allows us to reflect on the limitations, hierarchies, and idealities that restrict my hearing when it wants to obey a descriptive reference instead of plunging into the possible and diving into the possibility of the impossible.

A philosophy of sound does not follow an analytical philosophy of language but renders description secondary to the naming of its practice that takes care of the audible as the possible, the “what could be,” or indeed the “what there is” if we would only listen, and unlocks the possibility of the sonic impossible, understood as the as yet inaudible but nevertheless present sound. It is a philosophy that gives us access to what is there if we would look past the object into the complex plurality of its processes and materialities, the passing and unreliable nature of sound that does not fulfill its reference but makes its own.

If the sonic possible thing lacks language adequate to express its essence, the sense of its experience, rather than describe its source and properties, the sonic impossible thing lacks listeners even, but it nevertheless has an impact and thus is worth considering. It is worth talking about and listening out for, since, this is where, out of inaudible strands of sound the impossible but nevertheless real emerges and makes the audible sound.

Ed Pinsent | The Sound Projector

Bat and Person Dyning

Have you ever heard of a bat detector? The UK’s Bat Conservation Trust knows all about them, luckily, and it turns out there are a wide variety of these electronic devices which can allow us to hear the ultrasonic sounds made by these little black-coated gentlemen with their lovely leathery wings. The devices work in many ways to make audible that which is normally inaudible, including time expansion (slowing down the original bat sound) and frequency division (dividing the frequency rate of the sound); but all of them use the principle of heterodyning, that is mixing the original bat frequency with another frequency, and (through some clever method of sums and differences) presenting a sound that is within the range of the human ear. Every home should have a bat detector, even if you don’t have bats in your garden nor anticipate encountering any in the park. Eisuke Yanagisawa (film-maker, researcher and field recordist) has used one to make the record Ultrasonic Scapes (GRUENREKORDER Gr081). He started off with bats right enough, but soon applied it to cicadas, and thence to all sorts of electrical devices found in the street – including automatic gates, street lights, TV sets…in fine, just about anything that emits ultrasonic frequencies. Some of these sounds he blurts back at us are really intense and surprising, like particularly harsh forms of digital noise music, and even when not so intense they have a very compelling presence. Given its rather serendipitous nature and general lack of structure, you could never mistake this for electronic music, but on a purely aural level I can sense it would appeal to anyone who enjoyed what Stockhausen did with the ring modulator in the 1960s and 1970s. It’s also a rather process-based approach of course, and sometimes it seems more like a demo CD for a bat detector. While I personally would have liked to hear more utterances from the bats and the insects, the street noises are quite impressive too. A good listen – fascinating material which reveals an unheard world that is all around us, yet largely unknown.

rm | Gonzo (circus) #106

Aurelio Cianciotta | Neural

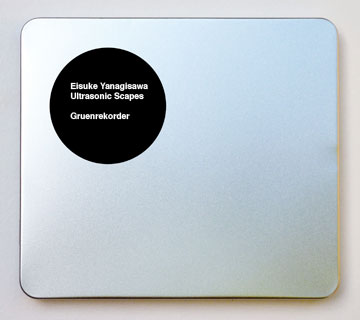

Eisuke Yanagisawa, an audio-artist interested in field recordings and researching ethnographic matrices (the latter also explored through interesting cinematic experiments), has been studying the linguistic and cultural characteristics of rural Vietnamese since 2006. The results of these studies have helped create an ethnographic movie about gong culture and three experimental films about specific acoustic environments in Kyoto. „Ultrasonic Scapes“ is basically a documentary investigation, but it is oriented towards the universe of the non-audible; the sounds beyond the range of human hearing, the frequencies that the human ear barely perceives and cannot process. The intense sounds that we can hear in the ten recordings – hums of cicadas, machinic drones, beating bat wings, field recordings in the street – have been captured and converted in real time with a bat detector, a device that converts ultrasonic signals into audible sounds. The sounds are intense and continuous demonstrations of perception, even though they are translations of the original data, transcending any specific natural or inorganic origin. None of the tracks have been processed in any way (excluding small amplification of volume). The recording is presented in a very nicely designed metal case.

Ron Schepper | textura

Issued in a 50-copy run as part of Gruenrekorder’s Field Recording Series, Eisuke Yanagisawa’s Ultrasonic Scapes makes a strong argument for the accessibility of the field recordings-based recording. It does so by doing two things in particular: drawing upon diverse subject matter in its ten tracks and by presenting its contents with concision, as the CD squeezes its material into a lean thirty-five-minute running time. What we get, then, are snapshots that whet the appetite for more of Yanagisawa’s alien-sounding material. It must needs be said, however, that although the tracks were captured in real time and were left unprocessed except for a little amplification, the sounds are not natural in the wholly unmediated sense as they’re ones that exist beyond our audible range, Yanagisawa having recorded them using a bat detector—hence the Ultrasonic Scapes title. It’s another in Gruenrekorder’s “silver box” releases, with Yanagisawa’s CD-R, like those that have come before, housed within a shiny metal case and accompanied by sleeve notes printed on a translucent sheet.

As a field recording often does when the visual component is stripped away and we’re left with raw sound, Yanagisawa’s material sometimes casts the natural phenomenon in an entirely new light. “Bat Calls,” for example, brings into sharp relief the rhythmic side of the creatures‘ echolocation in such a way that, as strange as it might sound, the micro-percussive chatter comes across as rather Autechre-like. And with its title removed, “Cicada Chorus” could as easily pass for the amplified sound of an overhead plane, the locomotive chug of a train engine, or the fire of artillery weaponry as much as a seething chorus of buzzing cicadas. Likewise, “Street Light#1” uses street and store illuminations as sound sources in a piece that could be heard as the amplified soundtrack of a heavily frog-populated pond. Ringing bells and muffled clatter of varying kinds dominate “6th Floor,” which was recorded at a department store near Shijo Station in Kyoto. A skeletal drone emerges when Yanagisawa applies his bat detector to the CRT-based “TV” in his room, while loops of scratchy flickers and clicks emerge from the innards of his PC during “Dell.” Admittedly a sound purist might quarrel with the naturalness of the results, given the manner by which Yanagisawa captured the tracks‘ sounds. The results speak for themselves, however, and the micro-universes presented on Ultrasonic Scapes are often compelling.

Nick Cain | The Wire – Issue: #332

Recently there has been an upsurge in the use of field recordings by a range of practitioners. One of its most vexing traits is the frequency with which the recordings are treated to fit the requirements of an existing vocabulary, whether it be Noise, drone or electroacoustic Improv, draining them of locality or character. German imprint Gruenrekorder’s Field Recordings series offers a haven of site-specificity. The label also runs Soundscapes and Sound Art lines, whose releases subject field recordings to various compositional or conceptual strategies. The 30 or so Field Recordings CDs mostly contain unprocessed location recordings. The results can be hit or miss, but this pair of discs are two of the series’s more rewarding entries. Eisuke Yanagisawa’s Ultrasonic Scapes collects ten recordings of ultrasonic (beyond human audio perception) sounds, made mostly in Kyoto with the help of a bat detector, and presents them untreated save for slight amplification. There are a couple of nature recordings: bat calls (unfurling patterns of click-tones), and a noisy cicada chorus. But mostly Yanagisawa is interested in listening to the hidden sounds of electronic devices and urban public spaces. White noise frequencies are ever-present, flecked with granular detail (presumably a by-product of the technology used). Elsewhere sounds cohere into repetitive patterns: the dull grinding of a street light, the rhythmic click of an automatic gate, or the hum of a TV. There’s a delightful series of tonal tinkles and pings in “Furin”. But most of them are almost comforting for the degree of structure they reveal – a kind of mundanity in the imperceptible.

UK recordist Tom Lawrence finds similar certainties in a very different environment. Water Beetles… is a collection of underwater recordings from a 550 acre untouched marsh in Co Kildare, Ireland. In his notes Lawrence explains the historical and geographical context for each of the tracks, as well as the compositional processes he’s used – mostly simple montage or timelapse editing, blending different recordings from the same location with great sensitivity. The sounds he uncovers are often repetitive or constant – the klaxon buzzings of water beetle stridulations; the beat-pulsing frequency of a corixid water bug’s song; the clacking rhythms of a whirligig beetle’s alert call – yet all are fascinating for the detail they reveal about this submerged world. Lawrence’s respect for the sonic richness and narrative integrity of his chosen environment is palpable.

Dan Warburton | PARIS Transatlantic Magazine

Though this release, like the Tom Lawrence disc mentioned above, is part of Gruenrekorder’s Field Recording series, there’s no way you could actually ever hear the sounds it contains in a field, or anywhere else for that matter, since, as the title makes clear, they lie outside the range of human hearing. „All ultrasonic sounds were captured and real time converted by a bat detector,“ writes Yanagisawa, so it’s not surprising the disc kicks off with four and a half minutes of.. bats, which, when „converted“ (transposed down, is that?) produce a strange and rather attractive fluttery clicking. Of course, you’d never know you were listening to bats if the record liners didn’t tell you, but you might just be able to guess that the second track is a „Cicada Chorus“. It’s certainly more fun to listen to than the dull clicking of „Automatic Gate“ and the monotonous buzzes of Yanagisawa’s Dell computer. Marginally more interesting are the ultrasonic bits and pieces the detector manages to pick up from more „normal“ (audible) sound environments: a television, a set of wind chimes, and a busy street in Dogenzaka, where all the machine seems to capture is the muffled jangle of keys in pockets along with some odd shuffling sounds I assume to be Yanagisawa’s footsteps. Not that I really care that much. Unlike the Lawrence disc, which I’ve returned to several times because I think it just sounds great, this stuff tries the patience after a while. Once the initial novelty has worn off, there’s little to hold the attention in the way of music. Again, forgive me for using the M-word here (maybe someone would like to explain coherently once and for all what the difference is between „music“ and „sound art“), but this is a CD on a record label and has, presumably, been released in order to provide some sort of listening pleasure, or edification, to those who purchase it (and maybe a modest sum to its „creator“). The omnipresent grainy buzz – presumably that’s the bat detector – irritates, and there’s little behind it I want to listen to it again.

Joshua Meggitt | Cyclic Defrost

There’s a danger with albums that focus on particular processing devices in the music being subsumed by the process, restricting the sonic palette to an overarching awareness of the device or structure in use. Bat detectors pick up frequencies beyond human hearing, lowering them to human audibility presumably, a detail I’ve always found problematic – doesn’t changing the frequency in such a way completely alter the nature of the original source sound?

All sounds on Eisuke Yanagisawa’s Ultrasonic Scapes are derived from natural and inorganic sound sources captured with bat detectors, devoid of additional processing, and its actually quite a marvel. The opening sounds of, yup, bats, provides the obvious sonar pings and squawks one expects from these creatures, but the rest is united only by a kind of electronic creak typical of these devices. Cicada Chorus captures a rich buzzing beyond the frequency we’re used to hearing, creating vast dynamic swells. ‘Street Light #1’ and ‘Street Light #2’ create whining drones of varying tone and texture, while ‘Automatic Gate’ is a rhythm track evoking a mangy dog scratching itself on a sheet of reverberant cardboard. We also get grey hum from a TV and a Dell computer, commuter rabble in ‘Dogenzaka’ and the purely musical tin-can jangle of ‘Furin’ welcome bells, all of which reinforce John Cage’s dictum that silence is impossible to achieve – noise is indeed everywhere.

Richard Pinnell | The Watchful Ear

Today was a nice day. I had the day off of work and half intended sitting at my desk all day catching up on a large number of outstanding administrative tasks, but the day was lovely, warm sunshine woke me relatively early and so Julie and I headed off to the River Thames in West Oxford and after a walk along the banks sat and read for a good few hours, catching the sun a little and working up a thirst that we quenched at a nice riverside pub. The day was great, and then in the evening I went and met up with a friend for something to eat, though my enjoyment of the quite nice food was tempered by the bad music he insisted on playing throughout it. I got home late, but here anyway is a simple review of a CD I’ve played once or twice recently and then have been spinning since getting in this evening.

The disc in question is another release on the Gruenrekorder label, a further disc in their “silver box” series of field recording works. I call the series “silver box” because the releases each come in a silver CD sized tin, identical apart from a round black sticker on the front and a sheet of tracing paper containing track listing and sleeve notes inside. This one is named Ultrasonic Scapes and is a set of ten recordings by Eisuke Yanagisawa. The tracks here are field recordings, each captured in real time and presented as such here without any post production treatment, but the difference here is that they each are recordings of ultrasonic sounds usually inaudible to the human ear but captured and converted here using a bat detector, which I guess must apply some form of real time treatment to the sounds or we wouldn’t be now able to hear them…

So the pieces are fascinating. There are recordings of streetlights, automatic gates, a TV and other manmade electronic items, but also sounds captured from bats and cicadas and other pieces that, even though titled I cannot work out the source object for. Now as a piece of documentary exploration (and indeed the liner notes actually describe the release as “another soundscape documentary beyond our audible range”) this is interesting and quite surprising work. A kind of dull cloudy sheen of static fills the background of each of the tracks, thicker and heavier on some than others, but over this we hear a kind of brittle, stark sounds emanating from the various objects. Some pieces have clear rhythmic patterns driving them, and this seems, perhaps not surprisingly, to be the case with the manmade items, so the streetlights pulse with a kind of electronic sounding squelch and spluttering cough similar to an analogue synth fed through a Max/MSP gate of some kind. The eight track, Dell, which quite possibly relates to a recording of a computer hard drive resembles the kind of mysterious revolving distortion patterns often heard if you pay attention to shortwave radio frequencies. The bat recordings and the chorus of cicadas don’t have the same sensation but are both quite eerily unnatural in how they sound here, the cicadas in particular sounding more like an old steam locomotive picking up momentum as much as anything else.

So, as documentary recordings of this hidden world out there, as a way of revealing the mass of activity that we don’t normally identify with, this disc is a nice eye opener and a clever indication towards how vaguely musical forms can be found by accident in this manner.I fin myself asking the same question however that I have asked a number of times of late. Does good documentary make for good music? Is this CD enjoyable, or mentally stimulating when put on the stereo and listened to? What was the purpose of this disc’s release? Merely to highlight in a semi scientific way this area of sonic research or as something to be sat down and listened to considered as an artwork? Such thoughts are of course packed with loaded questions in themselves and indeed art, as with beauty is in the eye (ear) of the beholder- one person’s uninteresting idea is someone else’s conceptual masterpiece, but I can only present my own personal opinion, and for me these ten pieces offer me little that makes much in the way of a musical, or emotional statement to me. This isn’t to diminish the value of the work as interesting and perhaps important documentation, but for me where these pieces fall down, as something like Lee Patterson’s Egg Fry succeeded, is that they don’t really make for particularly riveting music. Once you get past the element of surprise at exactly what you are hearing, my interest wanes. Incidental, found musicality can be great, as the frying egg proved to me at least, but here on these pieces, with the exception of the momentarily more interesting clatter and chiming of a piece named 6th Floor, the way the sounds sit, generally just present and looping rather than evolving or decaying, isn’t that interesting over more than one listen. We come back again to a word I have though about often in relation to CDs of field recordings- purpose. What is the purpose of this music? What purpose was instilled into it by its composer? I sense little more than fascinated documentation, but I’d have liked to have heard something more.

Frans de Waard | VITAL WEEKLY

[…] Which also happened with the release by Eisuke Yanagisawa, who I assume is from Japan, and picked up the sounds of the cicadas, bats and drone sounds from street lights and feeds them through signal processors. He has a release before (see Vital Weekly 684), which seemed all more in pure field recordings, but this new one has unmistakenly a more electronic feel to it. That however is an illusion: all of these sounds were captured with a bat detector, picking up and translating sounds that are usually beyond the audible range. Ultrasonic sounds. Another pure documentation release, but slightly different also. In the case of Tom Lawrence things are very busy and nervous, with lots of things happening in the smaller details of the events, the release by Yanagisawa is more about static, single events captured very closely. Its also a more varied in terms of sonic approaches. Some very loud events are backed by some that are particular soft. This makes a varied release that is quite interesting and right to the point.

Brian Olewnick | The Bird Cage

Every so often, more so in recent years, a release passes across my desk and through my ears whose contents consist of unadulterated, unprocessed field recordings. Now, I have, I daresay, hundreds of recordings that utilize field recordings to one extent or another but even those wherein the entire contents are sounds picked up by a mic left out in the desert or beside a highway or within the hull of an old boat generally involve some degree of manipulation by the person involved, some sculpting, some design element. These can, in the right hands, be extraordinarily beautiful documents. I’m thinking of Toshiya Tsunoda’s „Scenery of Decalcomania“, for example. The choices he makes, the weight he assigns to the various elements work to create a composition which seems for all the world to be „just“ a recording of a scene but, in fact, is an idealized situation, a fictional world more incisively etched than what you’re likely to hear yourself, as a blank wall by Vermeer contains more in it than you’re likely to see, looking straight into one.

[…]

Eisuke Yanagisawa’s „Ultrasonic Scapes“ offers a case that is, in one sense, at an opposite end of things but in another, comes up against the same problem. He uses a bat detector to makes his recordings. One track, indeed, depicts bats while another goes after a choir of cicadas but the majority, eight out of ten cuts, pick up the faintly heard, to human ears, sounds of the industrialized world, including electric gates, street lights, muted TVs and computer innards. As with Lawrence’s disc, one is privy to sound environments normally hidden from, um, view although in this case, one imagine that, given a quiet enough space and the desire to do so, one could discern a good bit of it. But again, it’s presented „as is“, without manipulation or intent save for determining track length. Are the sounds interesting? Sure, for the most part, all of them, I suppose. Are they more interesting than what I can hear almost any time I want by merely concentrating on what happens to be within range? I’m not so sure. Granted, bats and cicadas aren’t flitting about at the moment, and the intensity level is pretty high here but I think we’ve all enjoyed a good refrigerator hum, savored the ultrasonics emitted when the TV is muted. I’ll be on a ferry this weekend and fully intend to lean up against the engine housing, letting the dull roar vibrate ears and body. The awareness of all the sounds around us which, surely, we’ve all been practicing to one extent or another at least since finding out who this John Cage feller is, makes experiencing a similar set of sounds through speakers a somewhat diluted event. Not only is, unavoidably, a good bit of spatial resonance lost but, as mentioned above, one feels a bit coerced down the recordist’s chosen path. It’s one thing, perhaps, to be so led in the course of a composed or improvised piece of music, another when it’s something apart from the person making the delivery. You’d somehow like to be introduced to an area, then let alone to discover things on your own, an impossibility, I guess, given existing technology.

This is not to say that either recording isn’t worth listening to. They are, in a way (The Yanagisawa more so than the Lawrence, to these ears), even if they leave me with an extremely unsatisfied sensation. They both succeed, as near as I can do, with doing what they set out to and do so admirably and attractively but I can’t shake the feeling that I’d rather dip my ear in a pond or press it up against a street lamp myself.

Gruenrekorder (Tom Lawrence, James Wyness, Terje Paulsen & Ákos Garai, Eisuke Yanagisawa, Ernst Karel) mentioned @ The Field Reporter / 2011 Final Report

A few words by The Field Reporter Editor Alan Smithee plus PART I of the lists with the most relevant works of 2011 made by our staff and other artists, curators and journalists.