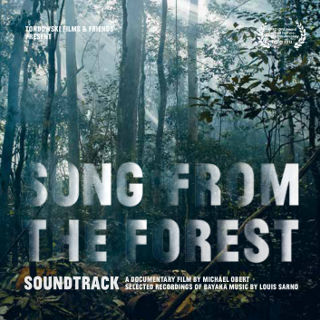

SONG FROM THE FOREST: THE SOUNDTRACK

SELECTED RECORDINGS OF BAYAKA MUSIC BY LOUIS SARNO

English | Deutsch

Gruen 150 | Audio CD > [order]

Digital > [order]

Reviews

This is the soundtrack album to the film „Song from the Forest“, which tells the story of Louis Sarno, an American who has lived for thirty years among the Bayaka pygmies in the Central African Republic. No outsider has had such access to this beautiful and musical culture, and this selection of the best of his recordings presents the sounds of this amazing people and their environment with a depth and richness never heard before.

SONG FROM THE FOREST: THE FILM /// Premieres in Germany: Showtimes

As a young man, the American Louis Sarno heard a song on the radio that gripped his imagination. He followed the mysterious sounds all the way to the Central African rainforest and found their source with the Bayaka Pygmies, a tribe of hunters and gatherers. He never left.

Today, twenty-five years later, Louis Sarno has recorded over 1,500 hours of unique Bayaka music. He is a fully accepted member of Bayaka society and has a son, Samedi. Once, when Samedi was a baby, he became seriously ill and Louis feared for his life. He held his son in his arms through a frightful night and made him a promise: “If you get through this, one day I’ll show you the world I come from.”

Now the time has come to fulfill his promise, and Louis travels with Samedi, age 13, from the African rainforest to another jungle, one of concrete, glass, and asphalt: New York City. Together they meet Louis’ family and old friends, including his closest friend from college, Jim Jarmusch.

Carried by the contrasts between rainforest and urban America, with a fascinating soundtrack and peaceful, loving imagery, their stories are interwoven to form a touching portrait of an extraordinary man and his son.

A modern epic set between rainforest and skyscrapers.

FROM THE DIRECTOR

In the fall of 2009, I was traveling in the Congo River Basin when by chance I heard tales of a white man who was said to have lived for decades in the rainforest with a tribe of huntergatherers called the Bayaka Pygmies, for decades. I went to look for him. A few days later, I was standing in a clearing when Bayaka came running at me from all directions, brandishing spears and screaming. Suddenly, the noise ceased, and a tall figure detached itself from the undergrowth: a white man, two heads taller than everybody else, a Bayaka baby in each of his arms. Before me stood a legend: a lost, forgotten man, reborn in the Central African jungle. A man who once ate tadpoles for a month, who married a Bayaka woman, who survived malaria, hepatitis, typhoid, leprosy, and has recorded more than 1500 hours of unique Bayaka music. Before me stood the musical Herodotus of the Central African forests, the white Bayaka—Louis Sarno.

When we shook hands in this clearing, I instantly felt that something really big had happened in my life. How could I know that this was the beginning of a journey which would turn me—a writer and journalist—into a film-maker and which would take me across the globe for years to come? To me—a person without a real home, driven from place to place, a passionate hunter-gatherer of stories who has spent the past twenty years traveling to the most remote corners of the Earth—Louis Sarno is the most fascinating person I have ever met. He took a radical leap, accomplishing what I often imagine myself doing when I am on the road: leaving it all behind, starting over, becoming someone else. More than everything else I am impressed by his life’s work: the fantastic recordings of Bayaka music that we are proud to present in this soundtrack from Song From the Forest. (Michael Obert)

FROM THE CURATOR

Beautifully mapping the entire range of music-making of a single community of hunter-gatherers across more than a generation, the Louis Sarno collection of Bayaka music and soundscapes is extraordinary, unprecedented, and unrepeatable. No field recordist has ever matched the depth and sensitivity of Sarno’s commitment to presenting a record of what it sounds like to live with an indigenous community. Sarno has developed a uniquely sensitive recording approach, refined through an acute listening that is only possible through permanent immersion in a culture.

Nearly all of the recordings on this soundtrack have been drawn from the Louis Sarno collection of Bayaka music at the Pitt-Rivers Museum in Oxford. Louis continues to donate his exceptional recordings to the Museum with the long-term intention that they will benefit the community whose musical life they so beautifully present. (Noel Lobley, Ethnomusicologist, Pitt-Rivers Museum, Oxford University)

FROM THE MUSIC SUPERVISOR

Through Louis Sarno’s recordings, Bayaka music has become famous around the world. I first spoke to Louis about his endeavours in the mid-nineties when I was putting together „The Book of Music and Nature“, which included some of his work. When I heard he was still down there, twenty years later, and that a film wasnbeing made about his life, I knew I wanted to help.

Central to Bayaka music is a sonic integration with the rhythms and melodies of the forest itself. We have tried to include selections from the vast archive that highlight the ways the human sounds fit into the natural sounds, as an inspiration for how human life as a whole might better be part of our surrounding environment, our true home. (David Rothenberg)

SOUNDTRACK

01. Yeyi-Greeting / 4:30

02. Women Sing in the Forest / 4:55

03. Tree Drumming / 3:08

04. Bobé Spirits Calling / 5:53

05. Bayaka Night Insects / 4:52

06. Louis Sarno Speaks / 2:32

07. The Flutes We Hear No More / 5:12

08. Net Hunt / 3:00

09. Earth Bow / 2:09

10. Geedal / 2:28

11. Flute in Forest / 5:16

12. Water Drumming / 2:55

13. Lingboku Celebration / 5:36

14. Moukouté’s Lament / 1:52

15. Yeyi-Farewell / 5:32

Excerpts:

Track 04

MP3

Track 07

MP3

Track 09

MP3

Track 15

MP3

15 Tracks (57′10″)

CD (1000 copies)

TRACK NOTES BY LOUIS SARNO

1. Yeyi-greeting / 4:30

Yeyi just means ‘yodel,’ and this is one of my favorite forms of Bayaka music. They used to go on all night, slowly moving through the village, and at dawn they’d be going on one last time, throwing leaves on the roof of each house. The new generation doesn’t do it the way it used to be done. This is the most recognizable sound in Bayaka music, pure vocal music, very beautiful songs. When they sing you can hear the forest all around them.

2. Women Sing in the Forest / 4:55

This is recorded in a bimba forest, where there is not much undergrowth, so you hear the singing echoing as if you were inside a natural cathedral. The Bayaka have this way of wandering into the forest, taking music from different forms, and improvising together as they collect water or gather mushrooms. I love the sound of women’s voices in the distance in the forest. The forest without that sound is incomplete. These are the most lovely voices on Earth.

3. Tree Drumming / 3:08

There is a certain kind of tree, the gooma that has big buttress roots. You hit it and it really resonates. Whenever the Bayaka come across a tree like this on the trail they hit it and play a little music. It’s kind of irresistible. Then they move on.

4. Bobé Spirits Calling / 5:53

I remember that camp, it was a beautiful one. The first evening, as the sun was setting, I saw this fire in the distance between the bimba trees. But it turned out to be the sun, at ground level in the forest, and you could barely see it through the trees at the horizon. The Bobé were really wild, spinning around and dancing wildly. That was the time when they buried Samedi’s grandmother. I had just came back from America, and I walked fifty kilometers in one day, and I heard she had died. The next day I set up to find this camp. We didn’t know where to go exactly, and it took us three days to find it. I was so moved by the place. The ceremony went on for two or three nights. This is a typical esimé, when the women move on from the usual melodic singing into something polyrhythmic. The Bobé are not human, they are animal spirits, and they use sounds that are beyond language. The Boyobi ceremony is not just music, it’s theater, dance, and myth, all blended together. Sometimes the Bobé spirits are naked in the moonlight, smeared with bioluminescent fungus. No crew has yet been able to film this!

5. Bayaka Night Insects / 4:52

Insects, yes, but also a few birds. That’s a type of cuckoo. I call it the „ngon go go“ bird. There are two cuckoos and the rest is insects, with maybe a few tree frogs. Sometimes you get these moments in the forest where everything seems to come together like that. That’s why I spent so much time in the forest, because most of the time nothing much seems to be happening. But once in a while you get these beautiful moments, which you can only get by spending a lot of time out there. Years.

6. Louis Sarno Speaks / 2:32

Ewunji was an incredible guy, Samedi’s great-grandfather. He was known to go very deep into the forest, way into what’s now the Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park in Congo, and we just wandered around with spears, no hunting nets. You couldn’t survive like that now. The small animals have been decimated by poachers. Taking care of this should be the responsibility of the World Wildlife Fund, but they prefer to concentrate on big charismatic animals like elephants and gorillas, instead of the animals that the Bayaka depend on, small forest antelopes and monkeys. The Bayaka are no longer allowed to go into the park, but the poachers still go in there with shotguns.

7. The Flutes We Hear No More / 5:12

That was the only time I ever heard two flute players playing at the same time. Momboli and Gongé playing mbyo duets on Dec. 22 nd 1992. You are supposed to hear this music in your dreams, that’s why they usually play it alone at night, so it can get into your dreams. They play more or less in unison even though the Bayaka love vocal polyphony. This is a music you no longer hear anymore, since the last flute player died a few years ago. He gave me his flute and I had it in my house and could get a bit of a sound out of it. But when the Séléka raided my house last year during the insurgency, they destroyed everything, and they smashed the flute. This is a sound we will never hear again.

8. Net Hunt / 3:00

Well, that’s not actually a net hunt. That’s actually gida-gida, it’s a gorilla hunting game, they imitate chimpanzee noises. That’s from 1987, the very first time I went out into the forest. Just the men and boys are singing here. They make these fake spears and pretend to kill.

9. Earth Bow / 2:09

To make an earth bow the Bayaka take a sapling and bend it over, then attach a piece of twine to one end of the sapling, tie the other end to a piece of bark and hold it over a hole that they dig in the ground. This was Boungingi, and those are the same guys who were playing the tree drum. Just takes them a minute or so to make this instrument. Usually one person plays it, but there is always some extra percussion in the background.

10. Geedal / 2:28

That’s Balonyona, one of the greatest masters of the bow harp, the geedal. I recorded many hours of his playing, he really was the best player of this instrument. In 1991 he even went to Paris to play. It has six strings, you find it all over Africa. But the Bayaka way of playing is a bit different. They use fewer notes, and more rhythms. They play along with the pulses of the forest. It fits right in.

11. Flute in Forest / 5:16

That is a beautiful melody, the flute sounds so beautiful in the forest in the distance. That sound brings back so many memories of so many good times. Momboli played that melody a lot, and I recorded it often in the distance. You hear the night ambience swelling with insects, frogs, cuckoos, and the distant flute. So many good times… This music is really part of the whole forest world.

12. Water Drumming / 2:55

When the women bathe, they are always playing water drum. And sometimes they get these percussive melodies, this is a music for girls, and they are much better at it than the boys. Women will do it, too, and sometimes I’ve been far away when you can only hear the deepest sounds, and I think it’s the drum, and when I get closer, I realize it is women playing in the water. It is one of the few instruments Bayaka women are allowed to play.

13. Lingboku Celebration / 5:36

Ah, the Lingboku – women’s music. That is the one spirit they still have. They claim all the others have been stolen from them by the men. A lot of the lyrics make fun of male sexuality, it’s really an expression of female power. The men don’t like women to do it. But they don’t stop them. The men are not supposed to be present when they sing it. “The penis has no endurance and dies right away, but the pussy is always ready to keep going.” You ought to mark this song “explicit” on the CD. The dancing is quite explicit, too, the women look like they’re humping each other and if they catch men looking at this they’ll chase them away.

14. Moukouté’s Lament / 1:52

Ah, that’s little Moukouté. He appears in the film. At the time you recorded him for the film, he really wasn’t all that good at the geedal. But since then, he’s gotten a lot better.

15. Yeyi-Farewell / 5:32

What can you say? It’s beautiful. Yeyi. It’s the most pure Bayaka music. I never get tired of hearing these songs. They bring back so much musical wealth of these people. I don’t make recordings anymore. In some ways it’s easier to make recordings with today’s new technology, but I don’t love it the way I love those old cassette recorders. How do you write numbers on those tiny SD cards! They’re always getting lost. Many of the people I used to record are no longer alive. The new generation is just not the same.

HELP THE BAYAKA

THE BAYAKA SUPPORT PROJECT

The Bayaka and their unique culture are threatened by the destruction of their rainforest home, poaching, and epidemics. Even before filming began, team members Michael Obert (director) Alex Tondowski & Ira Tondowski (producers) and Percy Vogel (associate producer) were looking for ways to support the Bayaka of Central Africa in their struggle for survival. These efforts developed into the Bayaka Support Project, which makes it possible for you, the viewers of Song From the Forest and the listeners to this soundtrack, to help the Bayaka through your donations. We will seek out projects that are appropriate and meaningful for the community and will help to develop them further. Please join the effort to support the Bayaka.

Donate today! Thank you.

Michael Obert, AlexTondowski, Ira Tondowski and Percy Vogel – Bayaka Support Project

Help by donating on our website:

www.songfromtheforest.com

SONG FROM THE FOREST

A documentary by Michael Obert

Michael Obert, director / Alex Tondowski and Ira Tondowski, producers / Percy Vogel, associate producer / Siri Klug, cinematographer / Wiebke Grundler, editor / Timo Selengia, sound / Marian Mentrup, sound design / David Rothenberg, music supervisor

Original Music – Louis Sarno recordings Archive of Bayaka Music and Sounds

© Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford. All rights reserved!

Soundtrack selections published by Mysterious Mountain Music (BMI)

© Tondowski Films & Friends and Gruenrekorder

Artwork: StudioKrimm / Photos: Matthias Ziegler

Further reading: www.piper.de

A large part of the profits from the sale of this CD will go to the Bayaka Support Project – Soundscape Series by Gruenrekorder

Germany / 2014 / Gruen 125 / LC 09488 / BMI / EAN 4050486913857

|

|

PROGRESS REPORT

Having not yet seen Michael Obert’s film the music here is from renders this harder to put into context, but going by what I understand from the accompanying booklet most of the songs originated from the Bayaka Pygmies in southwestern Central Africa. Each entry was recorded by the film’s subject, Louis Sarno, an American who one day, in the mid-1980s, became enchanted with such a song himself on the radio and not only took himself to the place in the Congo it was sourced from but ended up staying there, adapting to the Bayaka way of life, marrying a Bayaka woman, having children and recording over 1500 hours of music. It’s a compellingly unique story, saying much about the changing world as one individual’s quest to escape the west he grew up in in order to apply new meaning to his life a world away from those trust-funded travelers who take a year out to, uh, ‘find’ themselves. Although it equally arrives with a plethora of questions, it is hard to take away what Sarno has done to document his adopted tribe or draw attention to both their situation and that of others amongst their neighbours.

The songs here range from yodelling to simplistic combinations of chanting, percussion and stringed instruments being melodically plucked. Interspersed throughout are insect and other such sounds from the jungle, snatches of women singing amongst the trees, a game where chimpanzee sounds are emulated and, indeed, some narration from Sarno himself. Everything adds up to a whole as equally beguiling and compelling as, I’m sure, whatever that first song was Sarno heard on the radio before transforming his life. Whilst I won’t be following in his footsteps, I do now wish to see this film, at least. This stunning document, put together with great care and affection, couldn’t serve as a more suitable conduit for anybody wishing to expand their knowledge of those lesser charted places in the world around us. Superb. RJ.

link

Ed Pinsent | The Sound Projector

A Documentary Film by Michael Obert. Selected Recordings of Bayaka Music by Louis Sarno. GERMANY GRUENREKORDER Gruen 150 CD (2014)

Need an interesting solution to the problem of market saturation? Try marketing your charming recordings of an African tribe and their wild locality not as ‘World Music’ but as the soundtrack to a film about… a white American gone native. Add a varnished cover, fit for a mid-budget Hollywood project, copious and illuminating annotation along with rich illustration and bingo: something to compete with the eye-catching graphic design and oddball eccentricity of labels like Sublime Frequencies and Nonesuch Explorer.

I’m making this sound far more cynical than it actually is of course, and it’s purely a result of my own petty envy at the remarkable life experience of said American, the recording artist and film subject Louis Sarno, who tracked down the Bayaka pygmies after hearing them on the radio, then went on to become the only outsider (let alone westerner) to be inducted into the tribe. Since then he has amassed over 1500 hours of recordings, including rituals, musical performances and more personal mementos. His insider’s view might be seen as endowing ‘authenticity’, but it’s one with which we can identify from afar, given our awareness of issues such as poaching and land encroachment around the world.

In many senses these recordings – captured over the past thirty years of Sarno’s tribal residence – depict a disappearing world: that of the environment violated by greed, but also of the microcosm of tradition within the tribe itself. Several performances contain feature instruments or styles moribund (‘Geedal’), merely remembered (‘The Flutes We Hear No More’) or somewhat degenerated in the passing of time (‘Ye-yi Greeting’). Several juxtapose the human voice with the sounds of birdcalls, insects chirping and buzzing to highlight the immediacy of the environment for tribal life. Sound quality is mostly crisp, thanks to Mr. Sarno’s many hours of recording practice.

Most remarkable perhaps are rhythm-driven performances like ‘Earth Bow’ – a device consisting of a sapling bent over a hole, which delivers the kind of deep, resonant twang techno producers go crazy for – as well as on the tree and water drums (fairly self-explanatory designations), in the latter of which Sarno flags up the rhythmic superiority of the female drummers (it being one of the few instruments women are permitted to play), raising a gender-political message that has a more vocal outlet in ‘Lingboku Celebration’ – a song satirising male conservativeness, which is notable for its sexual explicitness.

Being the subject of the film, it’s fitting that Sarno gets to tell his own story halfway through. And quite a story it is: he relates the vivid sights, sounds, smells and tastes (the idea of raw honey is making me ravenous) he has encountered in the forest, all of which seem to electrify the senses as much as our Tesco and Primark-homogenised culture dulls ours. I suppose it’s rather easy to romanticise such things though. Louis Sarno found a life changing experience at the end of his quest, while Colonel Kurtz found ‘the horror’. We all have our own calling – not necessarily as colourful or adventurous as Sarno’s – but dispatches such as this (1) might at least embolden us to pay heed that there is a world elsewhere. (1) Including the film I’ve yet to see.

link

MASSIMO RICCI | TOUCHING EXTREMES

Determining signs must always be recognized.

Usually, when this reviewer spends time with a promising record that fails to deliver, another CD is placed in the player straight away in an instinctive gesture. And when the second item acts as an instant catalyzer of corroborative feelings and improved energies – in opposition to the “been there, done that” feeling related to the preceding listen – the lingering impression is that of having achieved an unexpected goal without lucky coincidences. This is exactly what happened with Song From The Forest. The invisible hand that pushed yours truly towards this magnificent disc had not given any advance information. What was learned, already at the first spin, is more important than merely memorizing the circumstances leading to the movie soundtracked by Louis Sarno’s recordings of Bayaka Pygmies, of which we find fifteen examples herein.

As an illiterate “fan” of Pygmy chanting (a kind of proto-minimalism, to quote Frank Zappa yet again), my meeting with Bayaka music conjured up visions of possibilities for an intelligently modest life. Something that most humans seem to have completely discarded, in their incessant quest for excessive wealth and ephemeral prestige, is surviving by following the truest laws of nature. Extracting mesmerizing patterns from found/invented instruments; welcoming a guest with masterfully interlaced melodies; making fun of the short serviceability of male organs in a mockingly sex-tinged, all-female tune. All practices that by now belong to forgotten spheres and places. This fusion of uncontaminated joy, admirably tuned vocalization, wooden and watery rhythms and environmental echoes is out-and-out curative. The room becomes a space for decaying beliefs to regain their integrity; failures and anxieties are waved off for a while. The Bayaka cosmos encompasses everything that has a pulse – animal or less – to shape the listener’s impermanence into substantial wonderment.

link

Curt Cuisine | skug – Journal für Musik

Wenn das Genre Field Recordings wie Pop funktionieren würde, dann wäre »Song From The Forest«, der Soundtrack zum gleichnamigen Dokumentarfilm von Michael Obert. So etwas wie ein Blockbuster, mehr als das sogar, ein kanonisches Werk, das einerseits alle Tugenden des Genres, zugleich all seine Stereotypen und Romantizismen vereinigt. Michael Oberts Regiedebüt ist eine Dokumentation über einen Amerikaner, der seit einem Vierteljahrhundert »im zentralafrikanischen Regenwald unter Bayaka-Pygmäen lebt und mit seinem Sohn, dem Pygmäenjungen Samedi, eine Reise nach New York City unternimmt«. Obert ist als globetrottender Autor und Journalist für »Geo«, die »Süddeutsche« und viele andere renommierte Medien einschlägig vorbelastet. Der Film wiederum wurde mehrfach preisgekrönt und natürlich knüpft sich daran ein Spendenprojekt, das der Erhaltung der Kultur der Bayaka-Pygmäen zu Gute kommt. Der Soundtrack schließlich ist, wie schon angedeutet, der Inbegriff eines Field Recording-Romantizismus: wir hören die Gesänge der Pygmäen, ihr Trommeln an den Bäumen, den Gesang der Insekten, ein polyphones Flötenspiel wie aus dem Lehrbuch der äquatorialen Folklorstik sowie viele Tribal Songs & Pieces, die fast ausschließlich eingängig klingen, aufgenommen noch dazu über Jahrzehnte hinweg. Zu allem Überfluss handelt es sich um Sounddokumente einer allmählich verschwindenden Kultur. All das ist über jeden Tadel erhaben, gar keine Frage. Aber eben darum regt sich Skepsis gegenüber dieser schlichtweg umwerfend schönen CD. Ist das vielleicht doch nur Befindlichkeitsfahrstuhlmusik für Ethnologen? Schwer zu sagen. »These are the most lovely voices on earth«, schreibt Obert über den Track Nummer Zwei. Wir hören, tief aus dem Regenwald heraus echoend, begleitet vom Zirpen der Grillen und dem Zwitschern der Vögel, die Bayaka-Frauen singen. Und das ist wirklich schön, ohne Frage. Selten hat es eine CD der geneigten Hörerin so leicht gemacht, die Augen zu schließen und an Ort und Stelle in eine schöne, unberührte, exotisch-märchenhafte Wildnis zu reisen. Vielleicht zu leicht, vielleicht eben darum diese Skepsis. Einfach zu schön dieses Album.

link

Aurelio Cianciotta | Neural

Everything starts with the movie by German director Michael Obert, Song From The Forest, a fascinating journey into the rainforest of Central Africa, organised in the fall of 2009. The notes of the release describe how Obert had heard the story of a white man who lived in the jungle among the Bayaka pygmies and he decided to go in search of him. Obert only later discovered that the man in question was Louis Sarno, an American musicologist who, twenty-five years previously, had left civilization to live in the wilderness area of the Congo and record Bayaka music. Over the years, Sarno collected more than fifteen hundred hours of recordings of Bayaka music, recently donated to the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. This film recounts his return to America. I don’t want to reveal too much of the plot. What matters in our opinion from a purely musical point of view is the intersection of the imagination of the project and its unique documentation, the result of a site-specific work certainly not aimed at those who listen today. Of course the collection of primitive polyphonic songs, interlocking melodies and tribal percussion is no longer completely new and can be found in similar ethnographic recordings. What appears here is authentic material documented “from the inside” and enlivened by Sarno’s own uncompromising rejection of the American way of life, only later developed into a kind of social and cultural criticism that is tangible in the movie.

link

Héctor Cabrero | Le son du grisli

La musique d’un film que nous ne verrons peut-être jamais. Jamais, même, c’est décidé. Un documentaire de Michael Obert sur Louis Sarno qui, lui, a enregistré pendant des heures et des heures encore (plus de 1500, lit-on) la forêt équatoriale de Centrafrique.

La déforestation menace la région mais elle n’empêche pas les pygmées bayakas de vivre et de chanter ni les animaux qui la peuplent d’appeller. Sarno connaît par cœur ces sons (qu’il explique d’ailleurs dans le livret) parce qu’ils font partie de son quotidien, composent son environnement sonore. C’est le secret de cette sélection que nous rapporte Gruenrekorder qui ne donne pas dans le sensationnel ou l’exotisme. C’est plutôt un enregistrement qui mêle le sérieux d’Ocora à la poésie du sensible captée par Sarno.

Les oiseaux le jour, les insectes la nuit. Pour le reste, les voix des pygmées. En groupes, ils s’accompagnent de coups donnés sur un arbre, d’une flûte, d’un instrument à cordes en plus des bruits de la nature. Surtout ils nous transforment en voyageur condamné, chez lui, à garder le lit. Heureusement ils nous visitent, avec ce Louis Sarno, et s’offrent en cadeau. Comme c’est réconfortant.

link

Idwal Fisher | IDWAL FISHER

Let us venture into the Central African rainforest which is where Louis Sarno found himself after hearing the music of the Bayaka Pygmies playing on his radio one night. And off he goes on what must have been an exciting and daunting journey. Twenty five years later Sarno is an accepted member of the community and has a son called Samedi. The film ‘Song From The Forest’ recounts how Sarno brought his son back to New York, from one jungle to another. What we have here is the soundtrack and but a small representation of the 1,500 hours worth of recordings that Sarno has made of the Bayaka Pygmies unique music.

And they do like to make music. When they pass a gooma tree they slap its exposed buttressed roots, when the women bathe they slap the water to make water drums, when they go into the forest they mimic chimpanzees in mock gorilla hunting games, they play flutes, bow harps, they sing laments, greetings and farewells and by the sounds of it have a good time in the process.

Listening to Song From The Forest you are struck by the purity of it all. An hour of this CD will cleanse your mind of years of commercial radio. Its the purity that William Bennet speaks of when he says that the sound of two African’s banging rocks together has the same intensity of a Whitehouse performance. You can hear that in the tree drumming where the driving polyrhythms are joined by a female vocalist who’s breathy utterances give the piece an air of [probably unintended] menace. ‘Earth Bow is another remarkable piece in which a sapling is bent with a piece of twine thats then plucked, a rainforest double bass, as ever accompaniment is in the shape of hand made percussion. ‘The Flutes We Hear No More’ is the sound of two duetting flautist, the flutes now destroyed and gone forever. The CD is bookended by both a greeting and a farewell. The Yeyi-Farewell is a haunting dirge that showcases the Bayaka’s penchant for polyphonic vocals, in-between the coughs and the cicadas emerges a lonesome and yearning voice.

As well as the Bayaka there are pure forest recordings and dialogue from Sarno recounting the story of someone he knew who could walk into the forest and live like a king on the food he caught and gathered. An amazing adventure and an amazing story. Makes not to self to see film.

link

Roger Batty | Musique Machine

Song From The Forest is the soundtrack from Michael Obert’s fascinating documentary about the Bayaka Pygmies of the Central African rainforest, & their relationship with American Louis Sarno who has lived with the tribe for some 25 years.

Over Sarno’s time with the tribe he has recorded over 1,500 hours of recordings of the tribe’s music, their singing, and the sounds of their every day lives. This soundtrack takes in 15 selections from Sarno’s recording archive, and these move between field recording, more musically/ rhythmic numbers, onto a mix of both field/musical tracks.

As one would expect from Gruenrekorder this release is wonderfully packaged. The CD comes in a digipak which takes in pictures of the forest the Bayaka live-in. Also you get a full colour glossy inlay booklet- this 20 page affair takes in pictures of the tribe & Sarno, write-ups about the project from various parties connected to the documentary, and the background to each of the 15 tracks featured.

The album opens up with the track “Yeyi-Greeting”. This takes in a recording of tribes beautiful ‘ yodelling’ like singing as many of the villages voices join together with the back drop of the night time forest sounds of insects & birds. Track three is entitled “Tree Drum”, and takes in the earthy & building sound of several people tree drumming with the addition of subdued vocalising.

Later on we have “Bayaka Night Insect” which features the detailed, layered & enchanting sound of the forests night time insect population, with the addition of the haunting yet tuneful cuckoo bird song. And “Louis Sarno Speaks” captures Sarno talking about his journeys into the deep forests with the tribe, with the backing of the forest bird song. Really each of the 15 tracks here is wonderfully capture & captivating, and with each new piece you feel like your getting pulled deeper into the Bayaka’s surroundings & life.

All told this is a highly captivating & interesting release, which mangers to be varied & rewarding through-out. I can see this appealing beyond the normal ‘field recording’ listener, as the quality & variation from track to track, the story behind the release, and the way the whole thing is presented.

link

Holger Adam | testcard #24: Bug Report. Digital war besser

[…] Dokument einer Reise ist auch der Soundtrack zum Film Song From The Forest, der den Amerikaner LOUIS SARNO porträtiert, der seit dreißig Jahren in Zentralafrika bei den Bayaka Pygmäen lebt. Ursprünglich angelockt durch die Musik des indigenen Volkes, reiste er in den Dschungel, um Ton-Aufnahmen zu machen und blieb. Der Film von Michael Obert, den ich noch nicht kenne, erzählt die Geschichte von Sarno, seiner Leidenschaft für die Musik der Bayaka und seinem Sohn Samedi, den er im Alter von dreizehn Jahren mit in seine alte Heimat, nach New York City, nimmt. Zum Film kann ich hier nichts weiter sagen, aber der Soundtrack, bestehend aus Field-Recordings der Gesänge und Instrumente der Bayaka im Dschungel Zentralafrikas, macht neugierig darauf, ihn anzuschauen. Der Soundtrack funktioniert allerdings auch ohne Film, und lässt eigene Bilder im Kopf entstehen, so wie auch die anderen hier besprochenen Aufnahmen. […]

link

Łukasz Komła | nowamuzyka.pl

„Song from the Forest” to nie jest zwykły soundtrack stworzony na potrzeby zwykłego filmu dokumentalnego. To fascynująca podróż w głąb lasów deszczowych Afryki Centralnej.

Wszystko zaczęło się od filmu pt. „Song from the Forest”, który nakręcił niemiecki reżyser Michael Obert. Jesienią 2009 roku Obert wyruszył w stronę dorzecza Kongo, wówczas – jak sam twierdzi – przez przypadek usłyszał opowieść o białym mężczyźnie żyjącym od wielu lat w dżungli wśród Pigmejów Bayaka. Postanowił, że go odszuka. I tak też się stało. Po kilku dniach wędrówki Obert natrafił na plemię Pigmejów, którzy wzięli go za intruza i starali się przegonić wymachując włóczniami, po czym z zarośli wyłoniła się postać białego człowieka o dwie głowy wyższego od Pigmejów Bayaka i trzymającego na rękach dziecko. Stanął przed nim Amerykanin Louis Sarno. – Kiedy uścisnąłem jego dłoń na tej polanie od razu poczułem, że spotkało mnie coś wyjątkowego w moim życiu – dodaje Obert. Ten film przedstawia też podróż Sarno i jego afrykańskiej rodziny do Ameryki. Historia tego filmu odnalazła swoje miejsce także w Polsce, gdzie podczas tegorocznej edycji Szczecin European Film Festival można było obejrzeć obraz „Song from the Forest” (pokaz odbył się 5 października).

Warto zadać sobie pytanie: jak Sarno trafił do lasów znajdujących się Republice Środkowej Afryki? Jeszcze jako młody człowiek usłyszał w radiu śpiew Pigmejów. To go utwierdziło w przekonaniu, że musi dotrzeć do źródła, czyli odnaleźć ludzi z plemienia Bayaka. Poruszony bogactwem kulturowym, jakiego doświadczył w trakcie swego pobytu wśród Pigmejów, stwierdził, że chce z nimi zamieszkać. Przez kolejne dwadzieścia pięć lat zarejestrował ponad 1500 godzin wyjątkowej muzyki Bayaka, oczywiście kosztem wielu wyrzeczeń. Opowiadał, że niekiedy musiał jeść przez cały miesiąc kijanki, przeżył malarię, zapalenie wątroby, dur brzuszny i trąd, lecz nie przeszkodziło mu to w podjęciu decyzji, aby ożenić się z kobietą Bayaka i mieć z nią dziecko.

Prawie wszystkie nagrania, jakie znalazły się na płycie „Song from the Forest: Selected Recordings of Bayaka Music by Louis Sarno”, zostały wyszperane z kolekcji Louisa Sarno znajdującej się w Muzeum Pitt Rivers w Oxfordzie, którą sam autor sukcesywnie powiększa.

Na płycie znajdziemy piętnaście fragmentów dokumentujących życie Pigmejów. W książęce dołączonej do albumu przeczytałem wiele interesujących komentarzy Sarno odnoszących do poszczególnych ścieżek. Już pierwsze nagranie „Yeyi-greeting” to zetknięcie się z fascynującą figurą wokalną o nazwie Yodel, zaś śpiew kobiet w „Women Sing in the Forest” – dodatkowo zanurzony w naturalnym pogłosie lasu, jest wielogłosową formą umilającą Pigmejom podróżowanie przez dżunglę i zbieranie grzybów. Zresztą Bayaka to lud trudniący się łowiectwem i zbieractwem. Muzykę perkusyjną odkrywamy w „Tree Drumming” – jak twierdzi Sarno – w lesie można spotkać pewien rodzaj drzewa, gooma, które ma bardzo duże korzenie. Ilekroć Bayaka natknął się na takie drzewo na szlaku muszą go dotknąć i zagrać na nim swoją muzykę.

„Bobé Spirits Calling” to rytualny taniec, teatr i żałobny śpiew kobiet po zmarłej osobie z plemienia. W tym fragmencie można dostrzec w głosach kobiet przejście od zwykłego melodyjnego śpiewu aż do polirytmicznych struktur. Zaś w „Bayaka Night Insects” mamy nocne odgłosy owadów i ptaków. W jednym z komentarzy Sarno podkreśla, jak ważną sprawą jest uregulowanie kłusownictwa szerzącego się od dziesiątek lat w tamtejszych lasach. W „The Flutes We Hear No More” z kolei mamy znakomity duet flecistów.

Jak iść na polowanie to tylko z Bayaka. W „Net Hunt” słyszymy Pigmejów naśladujących odgłosy goryli i szympansów, by móc je następnie złapać. To nagranie pochodzi z 1987 roku. Niemal transowe brzmienie instrumentu Boungingi mamy w „Earth Bow”, a pewien rodzaj miejscowej harfy usłyszymy w „Geedal”. „Water Drumming” przedstawia rytuał kąpiących się kobiet, gdzie słychać, jak całość przechodzi nie tylko w dobrą zabawę, lecz także pokazuje jeden z niewielu instrumentów Bayaka, na którym mogą grać kobiety. W „Lingboku Celebration” kobiety za pomocą śpiewu wyśmiewają męską seksualność. Ten rytuał jest wyrazem ich siły. Następnie męski głos na granicy lamentu („Moukouté’s Lament”) przechodzi w przepiękny polifoniczny utwór „Yeyi-farewell”.

Kolekcja nagrań Louisa Sarno jest niezwykła, bezprecedensowa i niepowtarzalna. Nie określiłbym Amerykanina jako producenta nagrań terenowych, gdyż on nie udał się tam jedynie w celu rejestrowania odgłosów puszczy i ludzi ją zamieszkujących. On wszedł w tą społeczność, zamieszkał, ba!, stał się jej członkiem. Sarno uchwycił i dostrzegł niebywałą wrażliwość wśród Pigmejów Bayaka. „Song from the Forest” to nie jest zwykły soundtrack stworzony na potrzeby zwykłego filmu dokumentalnego. To fascynująca podróż w głąb lasów deszczowych Afryki Centralnej.

link

Moritz Holfelder | Bayerischer Rundfunk

Soundtracks des Monats

[…] Dass zu einem Dokumentarfilm ein Soundtrack erscheint, kommt eher selten vor. Bei „Song from the Forest“ macht es aber absolut Sinn. Der Film erzählt die Geschichte von Louis Sarno, einem Amerikaner, der dreißig Jahre unter den Bayaka Pygmäen in der Zentralafrikanischen Republik gelebt hat.

Nie zuvor hatte ein Außenstehender einen so intimen Zugang zu dieser sehr musikalisch orientierten Kultur. Regisseur Michael Obert porträtiert diesen Louis Sarno, der in den 1980er-Jahren in den afrikanischen Urwald entschwand, um die Klänge und Rhythmen des Pygmäenstamms der Bayaka aufzuzeichnen. Deren Musik zählt inzwischen zum Unesco-Weltkulturerbe und Louis Sarno als ihr Archivar. Er blieb bei den Pygmäen und gründete dort eine Familie. Doch dann wollte Sarno seinem jugendlichen Sohn seine Heimat New York zeigen, ihm eine neue Welt eröffnen. Die Kontraste zwischen Regenwald und der US-Metropole prägen diesen Film.

Reichtum an Klängen

Der Soundtrack hingegen beschränkt sich auf die Töne im zentralafrikanischen Urwald: Insgesamt 15 Ton-Dokumente umfasst er mit Titeln wie „Frauengesang im Urwald“, „Baumtrommeln“, „Erdbogen“ oder „Wassertrommeln“. Ein ganzer Take ist allein der Musik der „Bayaka Nachtinsekten“ gewidmet. Diese Auswahl von Louis Sarnos besten Aufnahmen stellt den Reichtum an Klängen dieses einzigartigen Pygmäenvolks und seiner Umgebung vor. Auch wer den Film nicht gesehen hat, erlebt akustisch die Faszination einer für uns faszinierend fremden Welt.

Oft nur in der Ferne des Urwaldes im Blattwerk schwebender Gesang, dazu die rhythmischen Trommeln der Bayaka: Der Soundtrack zu dem preisgekrönten Dokumentarfilm „Song from the Forest“ – erschienen ist er bei Tondowski Film & Friends. In einem kleinen Booklet werden die Musikstücke jeweils erläutert – hinsichtlich ihrer Instrumentierung und ihrer rituellen Bedeutung. […]

link

Brian Olewnick | Just outside

Selected recordings from the soundtrack of Michael Obert’s documentary on the Bayaka Pygmies of the Central African rainforest. Some 25 years ago, Sarno, enchanted by music he’d heard on radio from this area, ventured there and ended up remaining, adopted by the Bayaka. The film, as I understand it, documents Sarno visiting New York City with his son, Samedi, 13 years of age.

The soundtrack album presents fifteen tracks culled from some 1,500 hours of recordings. I imagine many of us have heard various Pygmy music over the years though, speaking for myself, as entranced as I’ve been by what I’ve heard, I really know very little about it (even saying „it“ is likely pretty stupid as I’d suppose there are myriad kinds). The collection makes no claims as far as being representative and, approached thusly, as a sample of music and sounds that Sarno has experienced, it’s rather extraordinary. The jungle is always present in the form of insect and bird calls, sometimes, as in the track „Women Sing in the Forest“, the dominant element, the human contribution all but lost in the swarming cloud, other times, that’s all there is. There’s some extraordinary „tree drumming“ as well as the better known and no less amazing water drumming. There are flutes, „earth bows“ (a bent sampling with twine played over a hole in the ground acting as resonator, sounding like a bass doussn’gouni), bow harps and much singing, especially lovely when employing their version of hocketing („Lingboku Celebration“). Really a wonderful document with, thankfully, none of the sense of cultural imperialism one often finds, doubtless due to Sarno’s commitment to and immersion in the culture. Fantastic music and sounds, highly recommended.

link

textura

Louis Sarno’s story is an incredible one. As a young American, he heard a song on the radio that inspired him to venture to the Central African rainforest and locate the sounds‘ creators, the Bayaka Pygmies, a tribe of hunters and gatherers. But unlike most travelers, Sarno never returned home; instead, he became a fully accepted member of Bayaka society, married a Bayaka woman, fathered a son, Samedi, and over the span of twenty-five years recorded over 1,500 hours of unique Bayaka music, fifteen selections of which appear on this hour-long soundtrack to Michael Obert’s award-winning documentary film Song from the Forest.

Obviously Sarno is considerably more than a field recordist who temporarily visits a site to gather material with which to work in the comfort of a home studio. Song from the Forest presents instead a case of extraordinary immersion, the example of someone whose intimate relationship with an adopted world now affords others an invaluable glimpse into Bayaka Pygmies culture; Sarno’s liner notes for each track also provide valuable insight into the soundtrack content.

Some of the pieces exemplify a character that strongly roots them within their originating context. The close connection between the Bayaka Pygmies and nature comes through in “Yeyi—Greeting” in the purity of the yodeled chants that sing out amongst the dense thrum of forest insects. Even more haunting is “Women Sing in the Forest” where voices are heard echoing from the center of a bimba forest as the women collect water or gather mushrooms. In addition, a clear sense of place is conveyed by the whistling sound collage produced by insects and cuckoos within “Bayaka Night Insects,” “Net Hunt” documents the vocal sounds of a gorilla hunting game where men and boys imitate chimpanzee noises, and “Bobé Spirits Calling,” with its drums and chanting, exudes a feverish rhythmic pulse emblematic of a ritual ceremony.

In other instances, one can’t help but notice remarkable parallels that emerge between Western musical forms and those of the Bayaka Pygmies community. In fact, some pieces could pass for rough templates for dance music as well as other forms. The rhythms (and polyrhythms) beating through “Tree Drumming,” for example, generated when the Bayaka strike the tree’s big buttress roots, swing with a techno-like intensity, while “Earth Bow,” like some stripped-down techno-funk piece, weds a low-slung bass line to a syncopated percussive pattern and a 4/4-styled pulse. Striking too is “The Flutes We Hear No More,” which features Momboli and Gongé dueting in a way that’s not light years removed from the kind of two-part flute composition an American minimalist might have composed during the time of Steve Reich’s Drumming. Such surprising connections certainly seem to lend support to the idea of a universal grammar of sound.

link

Richard Allen | a closer listen

Listening to Song from the Forest, many older readers will think of the famous French duo Deep Forest. The duo helped increase interest in world music in the early nineties, but they also did the genre a slight disservice, creating an unfair association between native music and electronic beats. Song from the Forest – the soundtrack to the movie of the same name – is real world music, the sound of the Bayaka Pygmies as captured by Louis Sarno (with film direction by Michael Obert).

Sarno is the real deal. 25 years ago (the same time as Deep Forest became popular) – he heard a song on the radio and traced its origin to the Congo. Could “Sweet Lullaby” be the song he heard? If so, perhaps we should give the French duo more credit, because this recording is an inspiration, culled from over 1000 hours of tapes. Sarno now lives with the Bayaka, has a Pygmy son, and serves as an intermediary between the tribe and the outer world.

This is what it sounds like to be deep in the forest among the crickets and birds and hidden predators: beautiful and frightening, a small piece of the surpassing unknown. The song from the forest existed before it became Song from the Forest; nature sings its songs, and the Bayaka respond with their own.

The individual voices are intriguing, but the group dynamics inspire awe. These musicians interact and improvise, often using nearby objects (sticks, rocks) to enhance handmade drums. Polyphonic chanting and interlocking melodies abound. These songs are not performances, but expressions of tribal unity; the songs are who they are.

Sonic ephemera are interspersed: a walk through the forest, along with nearby monkeys (or Bayaka imitating monkeys; it’s not clear); a tranquil evening; Sarno’s description of the wonderful forest food. The more one listens, the more one appreciates the care that has gone into the selection of sounds; for those unable to see the movie, the soundtrack is the next best thing, bringing the forest to life. Just don’t call it world music; it’s Bayaka music, and it’s earned our respect.

link

Frans de Waard | VITAL WEEKLY

One of the various releases this week that is supposed to be a soundtrack. Here no film either, but just the recordings made by Louis Sarno, made in Central Africa with Bayaka Pygmies, a tribe of hunters and collectors. Sarno is not a visitor, but he lives there as a member and married, has a son and recorded 1500 hours of music and sounds. That’s what the documentary by Michael Obst is about, about this rather unique field recordist. Sarno, who guides us through music from Bayaka and the place they live in, documents each of the fifteen pieces here in word. Flutes, tree drumming, singing, games, celebrations and such like are what we hear on this disc. Sometimes recorded from a distance, with the rainforest adding a whole additional layer of sound, which works very well. The ‚Tree Drumming‘ reminded me of earlier Etant Donnes. I very much enjoy a release like this. Not because I know a lot about the subject of tribes or Non-Western music, and I am the first to admit I can’t say anything worthwhile about this, other than: I think this is a fascinating trip. Maybe it’s because I was on holiday just now, and perhaps I would like to evoke the memory of holiday a bit longer? (I doubt whether Central Africa will ever be a point of holiday for me however). Just for now I can really enjoy all of this a lot. Strangely fascinating music. A sound documentary as well as something that you can enjoy from a purely musical point of view. Very nice variation in the world of field recording.

link